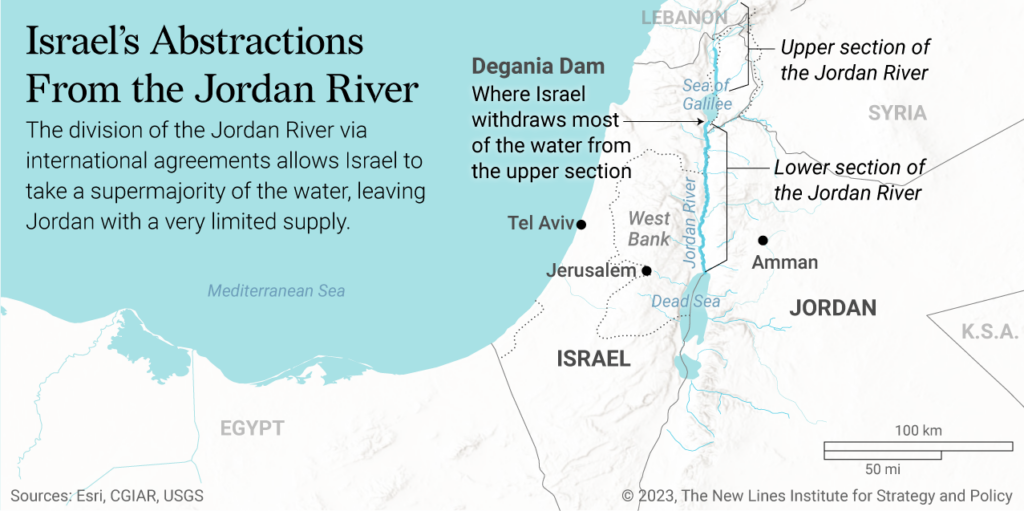

For decades, the United Nations and other international bodies have been discussing the Jordan River as though it were two entities, the “Upper” Jordan River and the “Lower” Jordan River. This is not just a question of semantics; the splitting of the Jordan River has perpetuated an inequitable division of water resources between Jordan and Israel, providing Israel with a significantly larger share of the basin’s waters. As climate change plunges Jordan even deeper into its water crisis, diplomats and environmentalists should abandon the artificial division between upstream and downstream waters, and diplomats should also reconsider the water annex between Israel and Jordan, starting with Israel’s hegemony over the upstream section of the Jordan River.

The division of the Jordan River into upper and lower sections has led to multiple problems in the region. Israel makes most of its withdrawals from upstream sections of the river. Even though these waters later flow through Jordan, the Palestinian territories, and Israel, serving as a border between Jordan and its neighbors to the east, the agreement between Jordan and Israel focuses primarily on dividing the downstream portions of the river while ignoring Israel’s upstream withdrawals. This division between upper and lower also has implications for initiatives that support the rehabilitation of the river. For example, in an agreement signed at the Conference of the Parties (COP27) summit of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Israel and Jordan agreed to a partnership to clean up downstream sections of the river; initiatives such as this will be more effective if the river is reconceptualized not as “upper” and “lower” but as a whole.

The United States has long played a role in negotiations over water use in the Levant, including providing leadership in developing the 1994 Israel-Jordan peace treaty, which established the legal framework for water division between the two countries. Following the cold peace between Jordan and Israel that has characterized much of their relationship, the two nations have begun collaborating more on water-sharing agreements and conservation efforts with support from the U.S., starting with their 2021 announcement of a water-energy exchange. These collaborations represent major shifts in the region’s approach to its water supply and present an opportunity for U.S. diplomats to continue facilitating Israeli-Jordanian diplomacy while advocating for an equitable and stable system for water allocation in the region.

Most crucially, U.S. diplomats should support Jordan in its efforts to get enough water for its growing population. Jordan, which has accepted over 760,000 registered Syrian refugees since 2011 (and nearly as many unregistered Syrian refugees), is a crucial U.S. ally. With 11 million people, Jordan’s population growth has increased the demand for water by about $600 million annually over the past 20 years. While both Israeli and U.S. policymakers have thus far been able to ignore the water crisis in Jordan, current environmental conditions render further neglect a dangerous possibility. Instead, policymakers should seize the opportunities presented at COP27 to reform the framework of water allocations in a way that is both equitable and sustainable. These steps are essential to ensure Jordan’s stability and prevent conflict in the region over access to water.

History and Current State

The lower section of the Jordan River begins at Lake Tiberius and converges with the Yarmouk River, which runs through Jordan. The river then flows through the Jordan Valley, where it serves as a border dividing Jordan from Israel and the Palestinian territories, and ends at the Dead Sea. These downstream sections of the Jordan River have seen massive reductions in flow rates in recent years. Estimates of annual discharge into the Dead Sea range between 20 and 200 million cubic meters (MCM) (about 4,400 and 44,000 million gallons), compared to the historic level of 1,300 MCM (about 286,000 million gallons) in the 1950s, prior to major hydraulic developments. The largest factors affecting flow rates are climate change and the amount of water Israel diverts before it ever reaches the lower section of the river.

Israel’s withdrawals of upstream water in the Jordan River Basin are largely made from the northern headwaters of the Jordan River, including waters in the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights region, which the Trump administration recognized in 2019 as being a part of Israel. The 1994 Israel-Jordan peace treaty divides the remaining lower section of the Jordan River between the two countries; the Palestinian territories are left out of the arrangement completely. The treaty implicitly upholds the upper/lower division of the river by only focusing on Jordan’s access to the river’s downstream waters. By failing to recognize Jordan’s entitlement to the upper section of the Jordan River waters, the kingdom’s water insecurity is perpetuated. In an apparent double standard, the peace treaty also states that Israel is “entitled” to a portion of water from the Yarmouk River, a waterway that runs through Jordan and Syria and feeds into the Jordan River.

While the peace treaty and the continuous water diplomacy between Jordan and Israel helped navigate conflict over water between the two nations, it failed to conserve and sustainably regulate sections of the lower portion of the Jordan River, which disproportionately impacts Jordanian and Palestinian communities. Flow rates, especially in the lower section of the Jordan River, have plummeted since aggressive hydraulic infrastructure projects began in the 1960s. Over the 30 years since the treaty was signed, Jordan has accepted over 760,000 registered refugees and its population has ballooned. As a result, Jordan’s water demand has risen, requiring it to purchase additional water from Israel. Further, environmental researchers have found “evidence of a changing ground reality” that would merit consideration in renegotiating a sustainable water agreement. The peace treaty likely accelerated the river’s degradation by facilitating access to it by both Jordan and Israel. Adequate water access is essential to Jordan’s stability and security. Among urban populations in Jordan, water is rationed severely below the per capita amounts recommended by the World Health Organization for people to maintain basic health and sanitation. Families frequently turn to expensive water tankers to supplement governmental water allocations, straining already low household incomes even further.

Seeing Double at the U.N.

The division of the Jordan River into upper and lower sections has proliferated among international bodies as well, including the U.N. Social and Economic Commission for West Asia (ESCWA). When bodies like the U.N.’s ESCWA study water quality, their conceptual division of the Jordan River obscures the sources of pollution and diversion. The Israel-Jordan peace treaty specified that both nations should “protect, within their own jurisdiction, the shared waters of the Jordan and Yarmouk Rivers, and (shared) groundwater, against any pollution, contamination, harm or unauthorized withdrawals of each other’s allocations.” In their 2013 report, which referred to the “Upper” and “Lower” Jordan River, ESCWA argued that the “flow of the Upper Jordan River into Lake Tiberius remains nearly natural.” However, ESCWA’s report fails to adequately emphasize that Israel’s upstream withdrawals are impacting the downstream water quality and quantity, resulting in severe stress in Jordan and the Palestinian territories.

The deterioration of the lower section of the Jordan River is impossible to understand without looking at the entire river basin. As a result of multiple nations’ dams, canals, and hydrology projects as well as climate change, the lower section of the Jordan River has declined into a polluted trickle. The regional organization EcoPeace Middle East estimates that of the 1.3 billion cubic meters of water that historically flowed into the lower section of the Jordan River annually, approximately 96% has been diverted by national authorities. In the downstream section of the Jordan River, only sewage, agricultural runoff, and brackish water keep the river from running completely dry.

These details are also important in the context of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Currently, Israel controls nearly all water access and distribution in the West Bank, a reality that Palestinians have been battling. In attempting to reform Israeli-Palestinian relations over water, Israeli water expert Hillel Shuval has proposed a system of shared water management that only covers the lower section of the Jordan River. But if limited to the lower section of the Jordan River, an Israeli-Palestinian deal would provide Palestinians with only a share of the 20 MCM that makes it past Lake Kinneret annually. For reference, Palestinians in the West Bank use about 200 MCM of water annually. This 20 MCM would represent less than 3% of the water that Israel abstracts from the upper section of the Jordan River and Lake Kinneret on average each year (about 700 MCM). This approach would resemble Israel’s peace treaty with Jordan, focusing only on the downstream portion of the river.

Moving Forward

The current water diplomacy arrangements between Jordan and Israel have failed to protect a historic ecosystem, with particularly high costs for Palestinian and Jordanian communities. In Jordan, low-income and refugee communities are grappling with high costs to get water. These communities are subject to water rationing. Across the river in the West Bank, many villages have had their taps run dry and animals die of thirst. In the long term, the lack of clean water could grow to destabilize and threaten the livelihoods and economic well-being of communities in the region.

Meanwhile, Israel’s technology, especially desalination, has enabled it to gain a water surplus, which it sells to Jordan. This demonstrates both Israel’s water security and Jordan’s water desperation. These dynamics should serve as a signal to both riparian countries and international bodies that the water annex of the Israel-Jordan peace treaty is due for renegotiation. The addition of these new desalinated water resources can change the situation from a zero-sum game to a positive-sum game.

In addition to the upper/lower divide, other flaws remain in the diplomatic agreements surrounding the Jordan River. For example, the water annex of the Israel-Jordan peace treaty entitles Israel to a set quantity of water from the Yarmouk, while stating that Jordan gets “the rest of the flow.” As climate change contributes to regional water shortages, Jordan’s remaining allocation will likely decline.

Renegotiating Jordan’s water rights should come in tandem with improvements to Jordan’s water infrastructure. The country loses about 50% of water that is supplied to urban systems to leaks, metering errors, and theft. Further, the kingdom has massive gaps in its water efficiency and water recycling programs, which USAID has stepped in to address. In the future, Israeli water experts should support their Jordanian counterparts to strengthen Jordanian water infrastructure and support their neighbors in conserving the Jordan River Basin. U.S. diplomats can lend their support to the process as well, facilitating collaboration between the two countries. U.S. diplomats have joined the United Arab Emirates in supporting the proposed water-energy exchange between Jordan and Israel, making them well-placed to lead further efforts.

These shifts in water needs and supplies merit inclusion in discussions about how environmentalists measure and conceive the Jordan River. Diplomats and politicians should reframe their understanding of the river to be more holistic and cognizant of human rights. Multiple international treaties, including the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, recognize the human right to water. Rather than focusing on absolute water allocations from the Jordan River Basin, future diplomatic agreements can be more equitable by focusing on per capita volumes of fresh water available to each country. The per capita approach would help reframe the discussion about water allocations, account for population fluxes, and uphold the human right to access water.

While this paper focuses on problems with the Israeli-Jordanian approach to water resources from the Jordan River, another glaring issue is the exclusion of Palestinians from joint management solutions. The Jordan River would serve as the border of a future Palestinian state, meaning Palestinians must be given a seat at the table.

In the past, the United States has played a leading role in facilitating water negotiations between countries that border the Jordan River. In addition to aligning water allocations with per capita water consumption, environmentalists, including one of the authors of this paper, have also proposed establishing a rules-based order to include a transboundary water management mechanism. These institutions will be important as nations move forward with their plans to restore the Jordan River.

Zoe H. Robbin is a Nonresident Fellow at New Lines Institute, where she leads the water connectivity and diplomacy initiative. She is a former Fulbright Research Fellow to Jordan. She has written for Al Jazeera, Foreign Policy, New Lines Magazine, the Daily Beast, and more. She tweets at @zoe_robbin.

Dr. Samer Talozi is an Associate Professor at the Jordan University of Science and Technology, where his research focuses on water resources, planning, and management at the national and regional levels. His work has been published in several journals, including Nature Sustainability, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Water Policy, and more.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not an official policy or position of the New Lines Institute.