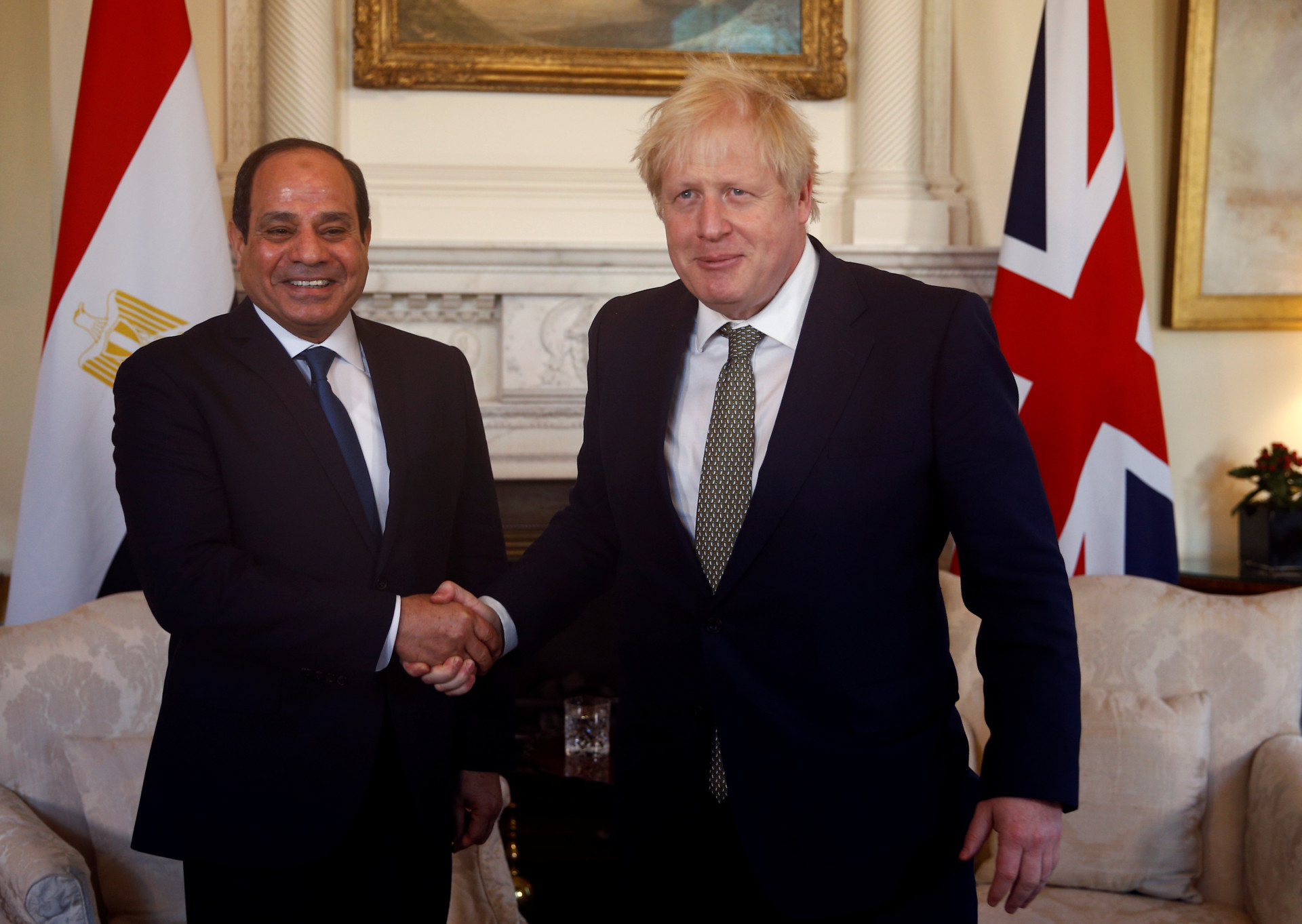

Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s government, more so than any of its predecessors since the Free Officers Revolution in 1952, appears to be trying to shape the human terrain of Egyptian society, popular culture, and politics in order to create a culture of national conformity. This state-led project indicates that the government intends to manage Egypt’s population with a system that manufactures consent – cultural, social, and political – and reduces violent confrontations between the state and the population.

The common perception that Egypt’s state and sociopolitics is dysfunctional belies the reality that al-Sisi’s government, and a successor administration, could very well use the country as a laboratory to test methods for state resilience amid the growing risk of autocratic meltdown that could be a distinguishing feature of the 21st century. Militant Islamist insurgencies in mainland Egypt in the 1990s, the Tahrir Square Revolution and the rise of the Muslim Brotherhood in the revolution’s aftermath, and nagging insurgencies in Sinai and its network on the Egyptian mainland were all challenges that the state confronted – and for the most part overcame – with the use of force. Prior to 2014, the Egyptian state could shoot its way out of its challenges, with the culmination of that era being the Rabaa Square military operation in August 2013 that resulted in more than 800 civilian deaths according to some estimates.

However, since 2014 the government has shown awareness of the limitations on its ability to meet every internal challenge with the use of force, with the most pressing challenges being the result of the combination of demography, geography, and resource scarcity. Although these challenges have existed for the Egyptian state for the last half century, the current government is contending with accelerating and exacerbating fundamental sociopolitical and socioeconomic challenges that will demand creativity. A dynamic to watch closely is if the Egyptian state determines that these challenges could be best served by an administrative, governmental, and security apparatus that makes decisions not through paternalistic networks but through centralized, state-run data-driven systems of distribution.

A Growing Population and Growing Fragility

The al-Sisi-led government and the wider Egyptian state have several advantages they can use to maintain relative control over Egypt’s population and territory and to exert influence in its near abroad. The state has a large military with a command structure that has a strong sense of asabiyya (group cohesion), control over advanced weapons systems, and a large, well-practiced, and proactive internal security and intelligence apparatus.

These security advantages allow the Egyptian state to divide and repress political opposition movements. For example, the state can wield influence over multiple significant religious entities, including Salafist groups such as al-Dawah al-Salafiyyah and its political wing, Hizb al-Nour, to counter a potential resurgence of the Muslim Brotherhood and its associates. Armed opposition movements in Egypt such as ISIS Sinai Province, Ajnad Misr, Ansar al-Islam, and Harakat Sawa’d Misr (also known as HASM) are significantly outgunned and unable to establish support zones except in certain remote locations, particularly the Sinai. The current government has also been effective at using Egypt’s strategic location along the one of the world’s most important maritime lines of trade to achieve sustained support from multiple foreign actors, including the great powers China, Russia, and the United States.

There are, however, complications that could threaten Egypt’s stability. Egypt’s large population is becoming too big to feed and more challenging to control over the long term, and urbanization and the concentration of the urban population means that when opposition movements become coherent there is a great risk of a snowball effect of disorder.

Egypt’s official population is approximately 103 million people, and it is projected to jump to 120 million people by the end of the decade. An estimated 95% of the population is jammed onto 5% of the country’s best and most fertile farmland along the Nile. Moreover, an estimated 2 million Egyptians (registered and unregistered) are born every year. Egypt is struggling to feed this growing population; the country imports the most wheat in the world as measured by tonnage in a period of growing global food importation costs, while it is one of the world’s most heavily indebted nations.

Sociopolitical pressures will continue to plague the al-Sisi-led government, too. Approximately 1 million young Egyptians (a significant number of whom are college educated) – especially young men – enter the job market every year but cannot find jobs inside Egypt and face dwindling prospects for economic migration in a post-COVID-19 global economy. Egyptian youths are also well-connected to the outside world, which adds torque to the social pressures for political and socioeconomic reforms that the state would have to manage with limited financial resources. Academic studies suggest that the strongest correlation between fragility and the outbreak of civil conflict is the presence of a large, educated, and underemployed male population, a fact that the Egyptian government is no doubt aware of and would remember well from the 2011-2013 unrest.

Further, water scarcity, desertification, and pollution are all stressors on Egypt’s population that are difficult to overcome, exacerbating the country’s social, economic, and infrastructural issues. The most difficult foreign challenge for Egypt, the construction and activation of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, is indicative of the environmental-resource problem that will vex al-Sisi’s government. The dam’s activation could decrease water levels on the Nile in Egypt, and that – combined with the salination of the Nile Delta caused by the rising levels of the Mediterranean Sea – could destroy Egypt’s agricultural economy. That, in turn, could lead to mass displacement and sociopolitical conflict that the state would not be able to manage. Third, armed opposition movements still exist in Egypt and are capable of carrying out attacks that are embarrassing to the state, could threaten the government’s massive infrastructure projects, and could metastasize into a larger armed opposition movement on the Egyptian mainland.

The costs of maintaining a population have led the Egyptian government to introduce austerity measures that reduce subsidies on and portions of bread and other basic goods. These measures are unpopular domestically but are required for Egypt to meet the demands of its international creditors. Although the Egyptian state applied austerity measures at different points before al-Sisi took power, the current government is linking these measures to population control. As al-Sisi has made clear in his communication with the Egyptian people, there is no greater national effort for Egypt than to manage its population size and drain on state resources; improve and systemize the means of production, importation, and distribution of essential goods; and leverage Egypt’s unique location with technological development to build an economy that can sustainably employ its people.

Use Big Data to Solve Big Problems?

Egypt is an ideal laboratory for a regime with strong internal cohesion and command-and-control but in a fragile environment to marshal a mixture of human and technological tools to service, secure, and shape its population. The tried-and-true police and internal security apparatus that previous regimes have used in Egypt is stretched thin by the country’s growing population.

It might not be feasible, in the event of future mass disruptions in Egyptian security, society, and politics, for the state to attempt to manage the actions of the population without the heavy use of technological tools. Ideally from its perspective, the Egyptian government would maintain authority without having to resort to mass arrests, extended incarceration, and violence, and would preempt destabilizing challenges to the state by shaping the population’s behavior as part of a national patriotic project assisted by technology and tradecraft learned from allied states.

Since the al-Sisi-led government came to power, the state has tested different technological tools to regulate the behavior of its population, especially cyber surveillance using cellphone applications. The current government has also sought to use popular ride-sharing applications, such as Uber and Careem, to develop big data on its population, and it has targeted profiles of certain members of the population – such as activists and journalists – whom it would seek to prevent from becoming sources of concern for the state’s security. Economic disruption for millions of Egyptians caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has also enabled the government to develop a better data picture of the country’s millions of workers in the informal economy through smart ration cards that allow the bearers to access state assistance. The government could use these technologies to perform reconnaissance on, categorize, service, and if needed conduct security operations against different segments of the Egyptian population.

Looking to China

Several Western sources provide Egyptian state security forces with supplies for maintaining security and surveilling the country’s population. However, China could be the model that the government turns to for learning essential processes for managing the population.

Arguably, the Egyptian state is far behind the Chinese state in terms of bureaucratic competences, internal information sharing, and efficiency in delivering services; providing security; and creating a coherent, unified, and networked command-and-control for managing the population. However, al-Sisi demonstrates a similar ethos to China’s Xi Jinping of placing the state-party (which in the Egyptian context is the alliance of the government and the military, security forces, and syndicates) as the vanguard of a great, multi-decade national project of renewal. The Egyptian government could therefore turn to the Chinese model for population management.

For example, China’s experimentation with a social credit system could find ready application in Egypt, where the government is actively trying to fashion a pervasive, data-driven system of social control to provide services for – and shape the behavior of – the country’s massive population. Some of the Egyptian government’s existing initiatives, meant to confront and bring to heel Egypt’s population boom and resource scarcity, are similar to earlier Chinese projects. The state-run Ithnayn Kafaya (Two Is Enough) program, an echo of the Chinese One Child Policy, is an initiative to educate Egyptians in general, and the poorest governorates in Egypt in particular, on the benefits of having only two children. The program particularly targets young families, and it is starting to provide vocational training, small business loans, and other types of support as perks for participation.

The Egyptian government could learn from the Chinese government and adopt many of the data-driven governance initiatives to confront the immense challenges facing Egypt. But the use of big data and machine learning that China has pioneered for managing, controlling, and preempting challenges from a restive population is just one component of this methodology. The other is a deep understanding of how to shape (or restrict) the discourse of the population and the overarching ethos that it follows. Al-Sisi’s persistent and public use of themes related to promoting order over chaos and building stability out of the instability caused by Egypt’s population growth, resource scarcity, and socioeconomic disparities do echo on a smaller scale what the Communist Party is seeking to overcome in China.

Al-Sisi is the lynchpin in this process. His background as the head of the internal intelligence branch of the Egyptian military, as the key military interlocutor with the Tahrir Square protesters, and as the defense minister in Mohammed Morsi’s government qualifies him to be the chief architect of a pervasive, targeted, and potentially effective system of population management. His upbringing in the heart of a popular neighborhood in Cairo, which no other Egyptian president who came from the ranks of the military has had, could also give him deep insight into the potential to harness Egyptian patriotism to achieve massive national goals. Moreover, al-Sisi and much of the leadership of the Egyptian security services came of age in the post-Camp David reality when internal challenges, rather than external ones, posed the greatest threats to the Egyptian state.

As in China, the policies being implemented in Egypt over the last half decade indicate that the government wants to shape and marshal Egypt’s population toward a national effort. The policies include limiting NGOs, expanding surveillance of the press and dissidents and using advanced technological methods to do so, issuing travel bans on political opponents, pressuring the president’s would-be electoral challengers to stand down from their campaigns, imposing state control over university students’ theses and dissertations, and shaping mass cultural content through state ownership of television and film production.

The marriage of an ethos of epochal national struggle, which al-Sisi is adept at communicating, with emerging socio-technological tools of population management, which the Egyptian state wants to master, clearly echo some of the key themes of China’s system under Xi that al-Sisi is well positioned to leverage. In the years to come, it would not be surprising if the Egyptian state adopted methods from Xi’s China. The military-led regime that has ruled Egypt since 1952 is not the same as the Chinese Communist Party, and the scale of the challenges in Egypt is not the same as in China. But Egypt could be an important testing ground for the methods and tools that China has pioneered for autocratic states to manage their populations and retain power in fragile environments driven by demographics, resource scarcity, and international competition.

Nicholas A. Heras is Senior Analyst and Program Head for State Resilience and Fragility in the Human Security Unit at the Newlines Institute. Prior to the Newlines Institute, he was the Director of Government Relations and the Middle East Security Program Manager at the Institute for the Study of War (ISW). Nicholas has authored or co-authored numerous reports and analytical articles on topics concerning Global and Middle East security issues, presented widely on these topics to multiple U.S. government and military agencies, and non-government organizations. He has been a frequent commentator to the media on Global and Middle East security issues. He tweets at @NicholasAHeras.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not an official policy or position of the Newlines Institute.