As conditions ostensibly stabilize in regime-held regions of Syria, officials in Jordan are more seriously considering the process of returning Syrian refugees. However, the current return strategy – mostly directed toward international NGOs, or INGOs, in refugee camps – fails to adequately track, include, or engage Jordan’s large contingent of urban refugees. Concurrent with this, policymakers should consider how midsized NGOs, currently excluded from a future Syria return strategy, can play a larger role in Jordan’s refugee space to ensure that return succeeds.

Midsized NGOs are embedded in cities. They can both decrease aid disparities between the camps and the cities and alleviate many of the operational difficulties faced by the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the Jordanian government. Most importantly, they can bridge yawning gaps between grassroots nonprofit work and return politics. As a partner nation deeply involved in Syrian border security efforts, the United States could benefit from midsized NGO activity at early phases of the return process. As such, U.S. politicians can assist each party by supporting midsized NGOs explicitly and encouraging greater cooperation between NGOs, INGOs, and municipal governments.

The Return Situation

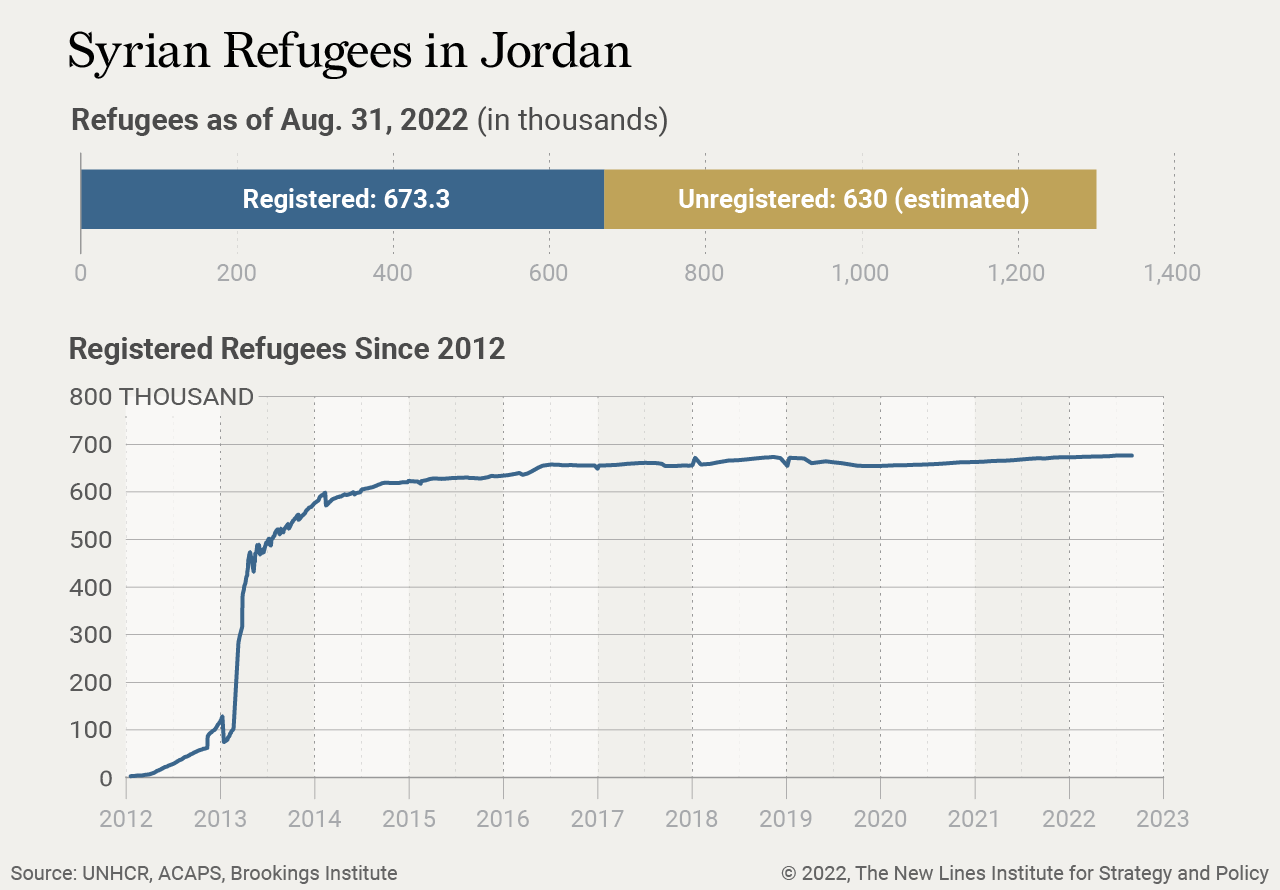

The approximately 13 million Syrian refugees scattered throughout the world are being scrutinized with a sense of urgency not seen in 11 years of civil war. The Syrian regime has regained control of most of the country, reducing active conflict in several regions and giving Syria’s internal conditions a veneer of stability. In response, several nations are mobilizing to begin the process of return and bring hundreds of thousands of displaced Syrians back home. Denmark became the first in March 2021 when it declared Damascus and its surroundings safe and began revoking Syrians’ visas. In July, Lebanon announced an aggressive plan to return 15,000 Syrians each month, pronouncing the conflict sufficiently stable to begin proceedings. One month earlier, The Washington Post reported an uptick in European tourists visiting regime-held Damascus, Aleppo, and Palmyra. And in Jordan, which has the second-largest Syrian refugee population (behind Turkey), return activity is once again becoming a politically charged issue.

The broad outlines of a return plan are well established, beginning with Russia’s 2017 proposal to create “safe zones” in western Syria. Consistent with this, safe settlement outposts and more robust humanitarian corridors have been identified as two additional requirements for returning refugees. At the heart of both suggestions lies the notion of secure transport, which bears several policy implications for the Jordanian government. First, Jordan must ensure that ground conditions in Syria are safe enough for refugees who want to voluntarily head back. They must be able to resettle without fearing political reprisal, violence, or the suppression of basic human rights. Second, Jordan will need to identify Syrians beyond those registered with UNHCR and establish protocols for tracking them over long periods of time. Third, it must convene an interagency task force to harmonize existing data on refugees and coordinate data-sharing nationally. Fourth, it must translate these steps into scalable procedures that can be adopted at regional and local levels.

In the short term, however, the pandemic, the war in Ukraine, and instability in Lebanon and at home have yanked resources away from the return question and rendered this impossible. COVID-19 continues to hamper growth and balloon unemployment, while the war in Ukraine has triggered widespread increases in oil, wheat, and grain prices. Ongoing turmoil in Lebanon presages a potential future influx of Lebanese refugees. Jordan will be obligated to accept this group under the non-refoulement principle established in its 1998 Memorandum of Understanding with UNHCR. And a swelling number of refugees already in Jordan remain unregistered, with current estimates hovering at 630,000 Syrians unaccounted for by UNHCR.

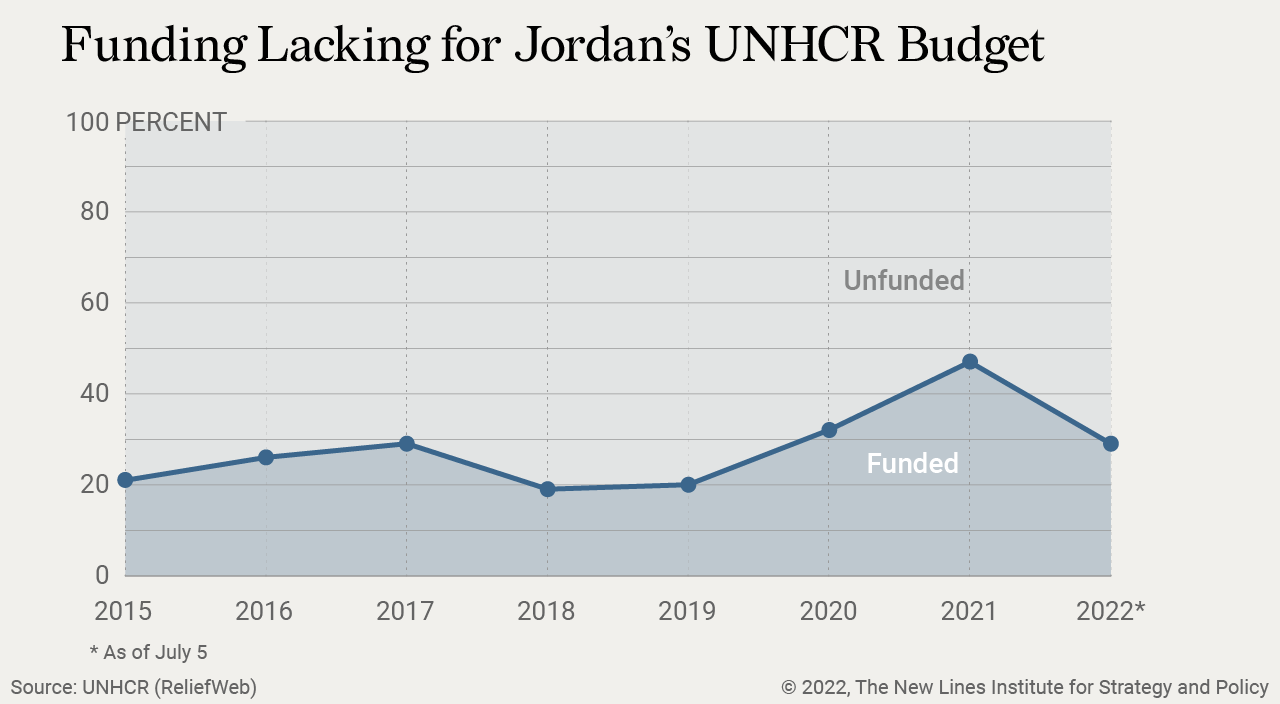

The resulting shockwaves have dealt severe blows to Jordan’s NGO sector. In apparent recognition of this fact, several INGOs downsized their staff in January after covertly obtaining exemptions to the government’s COVID-19 worker protection law, which prevented pandemic-related layoffs in the private sector. As Ukrainian refugees consume the world’s attention, waning interest from international donors has also forced NGOs to stretch their money further. According to Human Rights Watch, U.N. agencies in Jordan were funded only 47% in 2020, compounding existing gaps in strategic planning and humanitarian aid provision. With the population growth rate of Syrian refugees in Jordan projected to eclipse that of native Jordanians, this situation is poised to worsen. These deficits particularly will affect poor Jordanians, many of whom receive foreign aid through the same donations that primarily target Syrians. Left unaddressed, this population may see significant cuts in its already weakened funding networks.

Consequently, Jordan’s countervailing social crises have jeopardized its long-term resilience. Its refugee infrastructure threatens to buckle under the weight of the kingdom’s financial, social, and public health challenges, even as return politics loom. In the words of a 2020 report from the Ministry of Planning and International Coordination (MoPIC), the Syria crisis has hindered macroeconomic growth and “exacerbated […] security, economy, and social factors” in Jordan. Hemmed in by funding constraints but pressured to act, the Hashemite Kingdom does not have the tools to structure and focus its services on one refugee flow, then switch and refocus on others.

Moreover, Jordan has not developed complementary services to handle simultaneous inflows and outflows. The top-heavy construction of its refugee system has undermined civic reforms that could enable a more effective, nimbler response. This lack of institutional flexibility now threatens to blight Jordan’s refugee infrastructure at a critical moment.

In the Cities: Refugees and Midsized NGOs

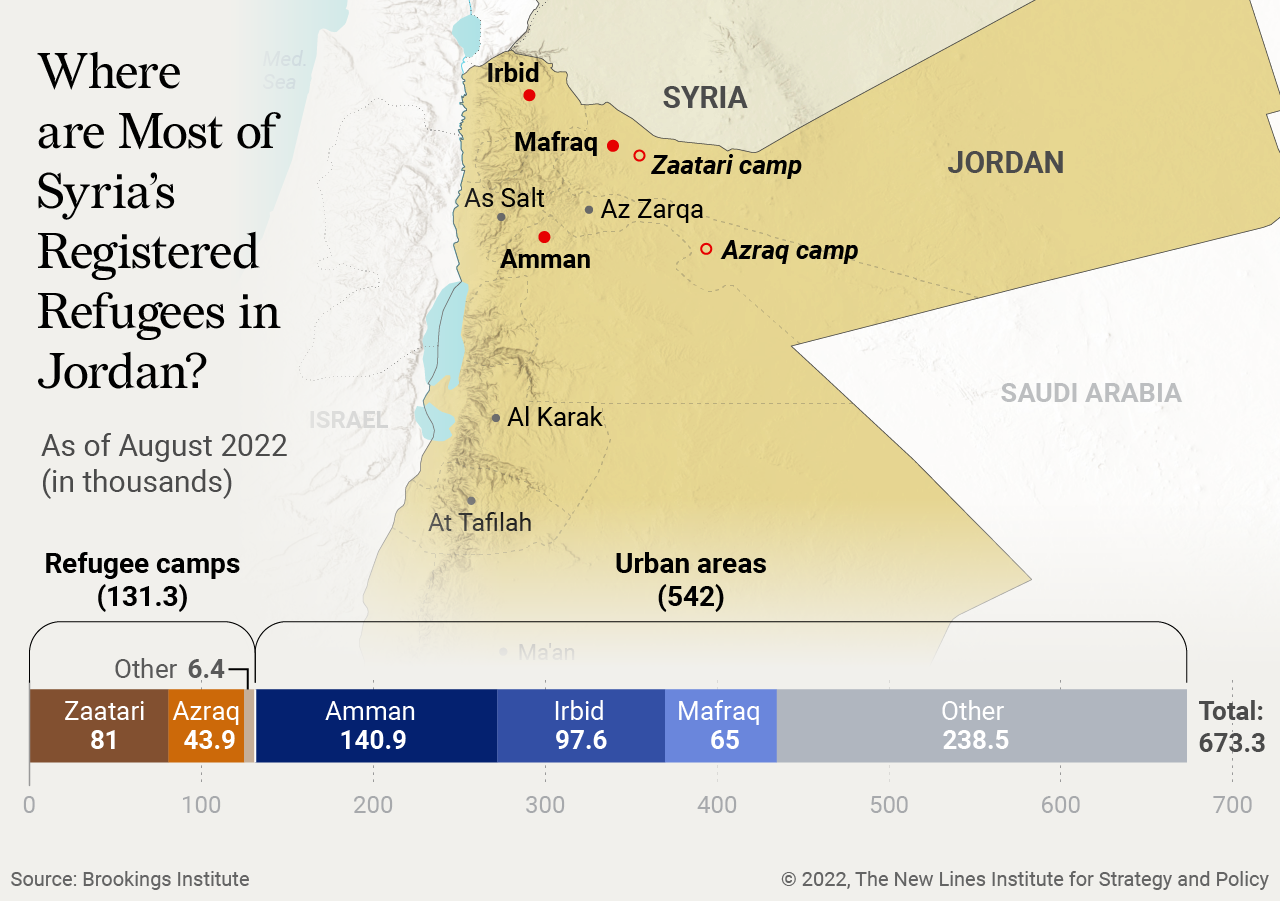

A precondition to any national return strategy will be resolving the aid disparities between the camps and the cities. Historically, the camps have received significant focus from both the Jordanian government and UNHCR, as well as corresponding international donor support.

By contrast, cities receive significantly less INGO focus or donor attention, and urban-based Syrians will prove the hardest to relocate. Over 80% of Syrian refugees now live in urban areas, making them both widely dispersed and difficult to locate. Complicating matters, UNHCR and the government of Jordan have no formal mechanisms for identifying, organizing, and transporting Syrians out of cities. As a non-signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention or its 1967 protocol, Jordan eschewed international frameworks that embed a national asylum strategy within core state structures, including blueprints for refugee protection and gainful employment applicable at the municipal level.

This lack of strategy is evident in urban refugees’ living conditions, which have declined precipitously since early 2020. In March 2022, a UNCHR assessment found that the number of urban Syrians living in unfinished or informal shelters has increased at least 6% between 2018 and 2022, with the majority in subpar housing. More than 55% of Syrians surveyed reported “severe vulnerability” in both economic and social dependencies, and rising food costs have driven collateral increases in malnourishment and poor health. Consequently, the number of Syrians who sought health care but could not get it has risen 13%. Together with a growing mental health crisis among urban refugees in Jordan, these data underscore the limits of state services.

The city of Amman, which houses 26% of Jordan’s Syrians, is a case in point. To date, it has not developed a comprehensive strategy for engaging with Syrian refugees or ensuring their access to basic needs. Its most recent Resilience Strategy makes no mention of refugees, and it addresses “migrants” only in the context of expanding youth employment programs to include them. Amman’s mayor, Yousef Shawarbeh, acknowledged refugees explicitly as a major challenge in remarks delivered at the U.N.’s Fifth Local and Regional Governments Forum on the 2030 Agenda. However, he focused more on long-term objectives than on uplifting refugee populations. Shawarbeh’s position echoes widespread sentiment that Syrian refugees are a hindrance to, rather than an element of, urban society.

The upshot of this activity is an urban space that has soured on hosting Syrians yet lacks the policy means to repatriate them. Enter midsized NGOs: a prevalent yet overlooked swath of Jordanian society. Midsized NGOs encapsulate a range of legally distinct organizations in Jordan, such as civil society organizations, community-based organizations, and royal NGOs. Organizations such as the Jordan River Foundation, which focuses on community empowerment and children; the Arab Renaissance for Democracy & Development, which focuses on legal aid and social justice; and Tamkeen, which focuses on migration and labor rights, fall into this category. By law, all NGOs must register with Jordan’s General Union of Voluntary Societies (GUVS). However, midsized NGOs could hold the key to a successful national return policy. By developing and implementing hyper-local programs, midsized NGOs develop strong communal ties with Syrian refugees and a robust understanding of their urban communities. Consequently, they can bridge persistent gaps between grassroots refugee issues and the policy-level return debates on which refugees will soon depend.

First, midsized NGOs develop strong bonds with their communities. Through their programming and physical space, they compile and retain detailed lists of alumni and participants, as well as potential refugees they could work with in the same community. These lists inform estimates of both the number of refugees in specific city neighborhoods and the sizes of informal communities they maintain. Many times, these estimates are more accurate than those of INGOs or the government, especially given NGO workers’ familiarity with the refugees themselves. Indeed, familiarity with local communities underpins multiple relations of trust that midsized NGOs nurture within their localities, resulting in refugees’ heightened comfort with NGOs and interpersonal bonds between refugees and NGO staff and volunteers. In this way, nonprofits can amass knowledge of refugees’ related social problems and the potential means to solve them. The small scale and intimacy of their operations blur traditional silos between personal and professional ties.

These relations are strengthened by midsized NGOs’ programmatic flexibility. Inherent in nonprofit commitments to serve refugee communities are the twin challenges of geopolitical uncertainty and changing aid frameworks, which are themselves mirrored by changing donor politics. The labyrinthine geopolitics of Syria have introduced unavoidable ambiguity to NGO programming, which must accommodate sudden policy changes that can initiate or delay return. Refugees’ personal feelings on return complicate this further: According to UNHCR, 57% of displaced Syrians in Jordan, Lebanon, Egypt, and Iraq plan to return to Syria one day. Midsized NGOs, therefore, must design programs that advance urban Syrians socioeconomically without committing them to permanent residency in Amman or other cities.

Changing aid frameworks have also spurred programmatic flexibility. Whereas NGOs relied upon crisis management frameworks for Syrians from the early to mid-2010s, their responses have inexorably shifted toward sustained development solutions as the conflict grinds on. Both frameworks respond to different financial imperatives from the international donor community, meaning NGOs often prime their operations to switch between the two.

Midsized NGOs also create webs of community leaders, support staff, and peer NGOs with whom they can collaborate. Independent of official sanction, NGOs can leverage mutual aid networks and local services to obtain resources, implement programs, receive communal permissions, or advertise information. Moreover, as locally embedded organizations, midsized NGOs can rely on word-of-mouth outreach campaigns to generate communal interest or penetrate communities more densely. These networks directly impact NGOs’ ability to amplify messages or important information. Their holistic application to the Syrian return could produce the kind of secure transport systems the government currently lacks to move Syrians out of cities.

As with refugee initiatives, so with midsized NGOs: Amman’s city government has not convincingly pursued the type of strategic planning that could lead to their municipal success. According to two industry professionals consulted for this analysis, the primary form of interaction between them is project-based: NGOs present their proposals, and the city government approves or denies them. Contract negotiations occur outside of each city’s proverbial four walls and are mediated frequently by foreign development agencies. Nonprofits that do not have active projects do not frequently work with city governments, nor are they compelled to report to local agencies. In other words, urban governance vis-à-vis NGOs is largely procedural, with more substantive regulatory and planning authorities devolving, by default, on the Jordanian state.

To some extent, this is by design. In this process, each humanitarian relief nonprofit first directs its funding or project requests to MoPIC. MoPIC administrators then review proposals to identify their institutional needs and determine final approval. For successful proposals, MoPIC connects the sponsoring NGOs with other government ministries in sectors relevant to their work. At this point, implementation can begin. MoPIC and the Jordanian government monitor NGO activity through the Jordan Response Information System for the Syria Crisis (JORISS), a centralized online platform offering feedback and consultations as needed. Then, once the project is done, the NGO concludes its business with the government – closing the administrative loop and effectively removing municipal agencies from every part of the process. City councils thus exercise no substantive form of nonprofit management, collaboration, or oversight over nonprofits – even for nonprofits in their backyards.

Two problems flow from this structure. First, the logistical and operational bottleneck it creates at the federal level is not difficult to see. The JORISS system, introduced with the rollout of MoPIC’s Jordan Response Plan, concentrates resources and administrative duties for even small projects at high levels. This bloats federal systems and slows nonprofit activity, some of which may be time sensitive.

Second, instead of turning to NGOs, Syrians refugees often obtain services directly from the cities, forcing them into a double bind. On one hand, cities lack the kind of strategic planning, reporting, and tracking programs that could aid refugees in short- or long-term capacities. On the other, in the absence of broader social safety nets, urban refugees sometimes rely on informal employment or low-wage work, opening themselves to exploitation and playing into the hands of persistent social stereotypes that they are stealing jobs from indigenous Jordanians. The 2016 Jordan Compact sought to remedy this by regulating specific sectors and granting work permits to eligible refugees. It introduced a much-needed economic relief for urban Syrians. However, it is tantamount to a salve on a larger wound: It did not result in a corresponding donor boon towards municipal institutions that support return policies. Furthermore, it directed refugees’ attention away from the very NGOs most concerned with their prosperity.

How Midsized NGOs Can Help

The question of Syrians’ return has concerned Jordanian society since the start of the crisis. Consequently, the related question of INGO involvement has seldom been far from Jordan’s mind. Efforts toward melding the two are already underway. The Jordan Response Plan, the kingdom’s largest response effort towards Syrian refugees, focuses on the strategic level of Syrian refugee affairs; it provides detailed budget allotments and sectoral needs for both crisis management functions and socioeconomic development functions. Its target audience appears to be multinational nonprofits and federal operators. However, it does not address mezzo- and grassroots-level activity in detail. Moreover, the government has issued no supplementary guidance for implementing Jordan Response Plan policies in cities, towns, and neighborhoods. As such, municipalities have embraced inconsistent standards for refugee project implementation.

Midsized NGOs could help fix this. Beyond what either INGOs or government entities could supply, midsized NGOs would be able to provide suggestions directly anchored in their daily operations. The communal bonds, refugee lists, programmatic dynamism, staff, and expert understanding of neighborhood-level dynamics position midsized NGOs to advocate on behalf of return policies within their respective communities. For this reason, they must be more involved in creating those policies at the city level. Together with city governments, midsized NGOs could build on the GUVS database and create regional, municipal, or local logs of NGO resources, including vehicle access, donor circles, security setups, and strategic partnerships. At minimum, this will strengthen connections between each city, nonprofit, and the communities they can help return to Syria.

By no means does this imply inaction from the federal government. On the contrary, government assistance will be crucial. MoPIC could spearhead these efforts through two initiatives. By delegating more resources and responsibilities to, city councils could improve return mechanisms through greater participation in refugee issues. Their active case management could mitigate bureaucratic jams at the federal level and co-produce better projects with NGOs – each without undercutting federal oversight imperatives. And by including midsized NGOs more explicitly in strategic planning, those NGOs could provide key knowledge bases and messaging assistance. This could connect city planning explicitly to broader geopolitics, in which NGOs could have stronger input and stronger coordination with fellow nonprofits. These changes will be especially beneficial for major cities like Amman, which is empowered to enact its own legislation and sign memorandums of understanding with national institutions and international donors. A greater grasp of local dynamics could close persistent knowledge gaps in these negotiations.

To begin filling those gaps, city councils and midsized NGOs could jointly design a city-level system to democratize data-sharing among urban NGOs. JORISS is an instructive model, as is the nonprofit registration process within the GUVS. A digital, publicly available platform for lower-level projects could help aggregate refugee data and enable nonprofit actors to coordinate more closely with each other vis-à-vis return. More generally, data-sharing could prevent financial or programmatic redundancies among peer organizations, and it could serve as a valuable benchmark against which federal agencies and INGOs could cross-reference their findings. At the city level, finally, the granularity of this data could drive better and more flexible return policies, adapting in real time to local changes.

Recommendations

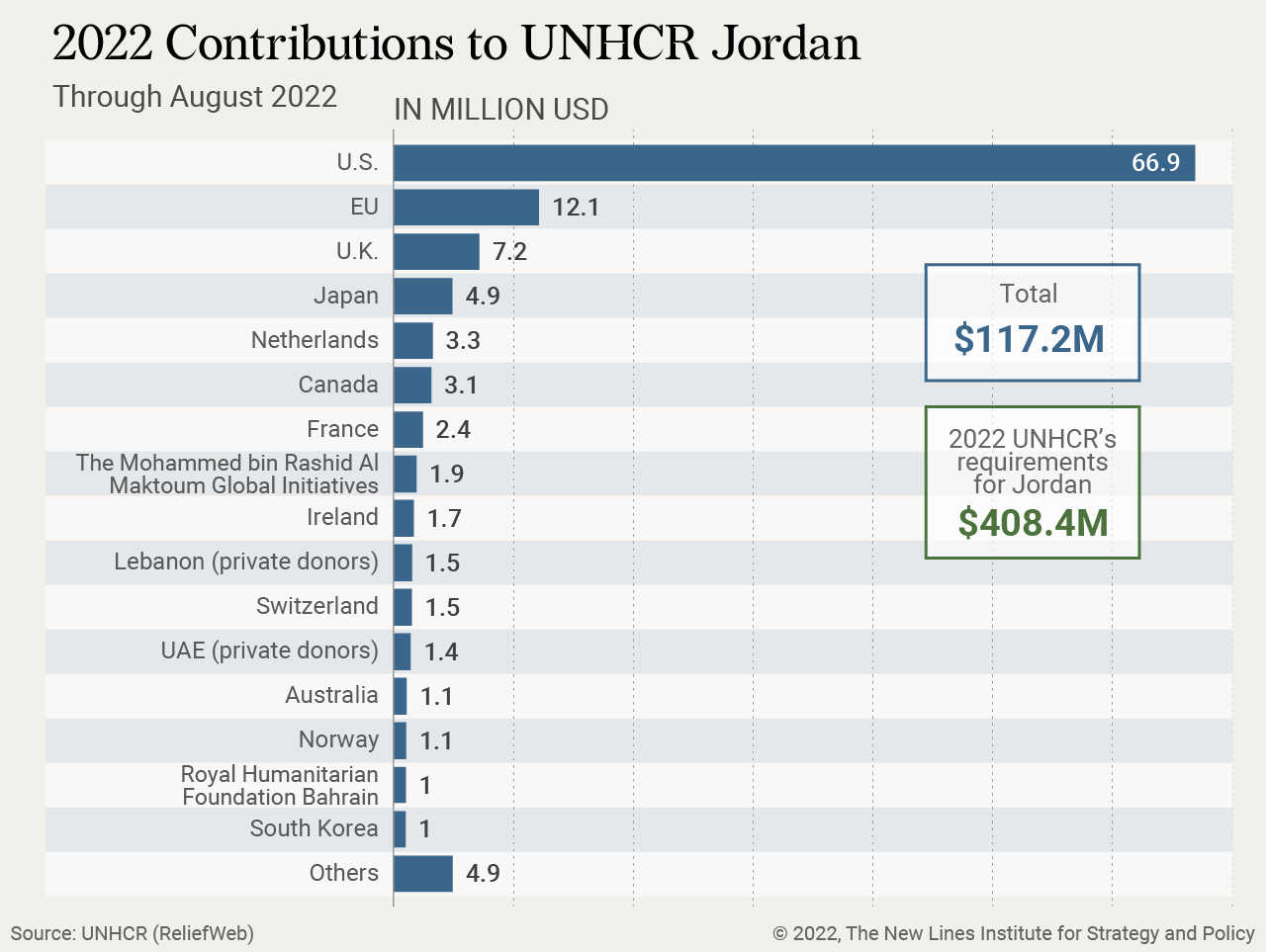

The United States, as Jordan’s largest provider of bilateral foreign aid, can play a significant role in supporting these reforms. It has already pledged roughly $15 billion in international aid toward the Syria crisis, most of which has been allocated to meeting the needs of Syrians who remain inside the country. Now, it must consider the other side of this process – return – and the ways in which helping midsized NGOs can amplify impact in preparing Syrians to head back.

This could manifest in several ways. First, the U.S. could directly support the NGO and security sectors by supplementing logistical or financial needs and identifying gaps that could maximize NGO impacts. From here, the U.S. could spur more nonprofit collaborations, hosting NGO leadership summits or providing seed funding for the digital infrastructures described above. U.S. Ambassador Henry Wooster could act as an intermediary between midsized NGOs, INGOs, and the Jordanian government to promote these measures. He could also liaise with city governments and encourage the adoption of political messaging that more explicitly uplifts refugees and promotes the creation of midsized NGOs to work with them. Through him, U.S. backing could lend considerable legitimacy to these efforts and streamline communication between midsized NGOs and larger entities.

The goal in both cases would be twofold: to focus on more horizontal coordination and to set favorable conditions for future vertical coordination between INGOs and their smaller urban counterparts. Horizontal coordination must be a precondition to vertical; it can form fertile ground upon which to build regional or municipal associations, leagues, and other groups among midsized NGOs. With American support, these larger groups could act as conduits for staffing, delegating, and implementing large projects. Alternatively, they could function as mutual aid clearinghouses for raw materials and services, transforming short-term resourcing into new cross-linkages and long-term, sectoral capacity building. The United States can help sponsor their creation by folding additional funding for city-level networks into its existing portfolios for Jordanian urban development, infrastructure, and resilience. These activities expand the footprint of midsized NGOs without expending further financial capital amid the NGO industry’s funding shortage. Furthermore, they do so without forcing NGOs to commit resources towards scaling up their operations, creating incentives for broader sectoral participation.

Midsized NGOs are positioned to be the next big players in Jordanian return politics. They can help humanely and efficiently repatriate Syrians in Jordan. They can also provide valuable assistance to broader efforts, and they can improve, if not revolutionize, the concerning downward trajectory of Jordanian refugee affairs. Refugees will not likely cause Jordan’s collapse – the country’s fiscal outlook remains stable. However, an absence of proper planning may create significant bureaucratic, economic, political, and diplomatic problems if left unaddressed. As a key U.S. ally, Jordan could benefit from a safe and compassionate return strategy that centralizes midsized NGOs, whose success could further stabilize Jordan diplomatically and economically. Policymakers should therefore consider incorporating midsized NGOs into mezzo-level refugee politics and in return politics writ large. It could achieve mutually beneficial ends: alleviating refugee affairs and giving more nonprofits a formalized place in Jordan’s aid architecture.

Gabriel Davis is the executive director of The Overseas Dispatch and a 2022-2023 Fulbright Scholar in Jordan. He received his bachelor’s degree in Middle Eastern Studies from the University of Chicago. He tweets at @gabrielssdavis.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not reflective of an official policy or position of the New Lines Institute.