The Ukrainian refugee crisis threatens the physical, psychological, and material well-being of all those displaced. While there has been overwhelming support for Ukrainians and global condemnation of Russia’s invasion, the economic pressures, security concerns, and domestic political tensions stemming from the crisis are likely to seriously affect regional states’ behavior and national interests. The EU, already contending with several other refugee crises, including from Afghanistan and Syria, was unprepared for Ukrainian refugees due to a lack of reforms that would help effectively manage migration and the rise of xenophobia and identity politics in many member states.

The U.S. and EU need an efficient, long-term plan for resettling Ukrainians amid a humanitarian crisis that could last years. The Biden administration has an opportunity to be a force multiplier by using its strong ties with its allies, international partners, and multilateral institutions to influence a coordinated European response to the Ukrainian refugee crisis. Advancing EU management of the refugee crisis is within U.S. interests of increased transatlantic cooperation on international security threats, as well as U.S. values of reducing human suffering and ensuring the safety of all people.

Status of Displaced Ukrainians

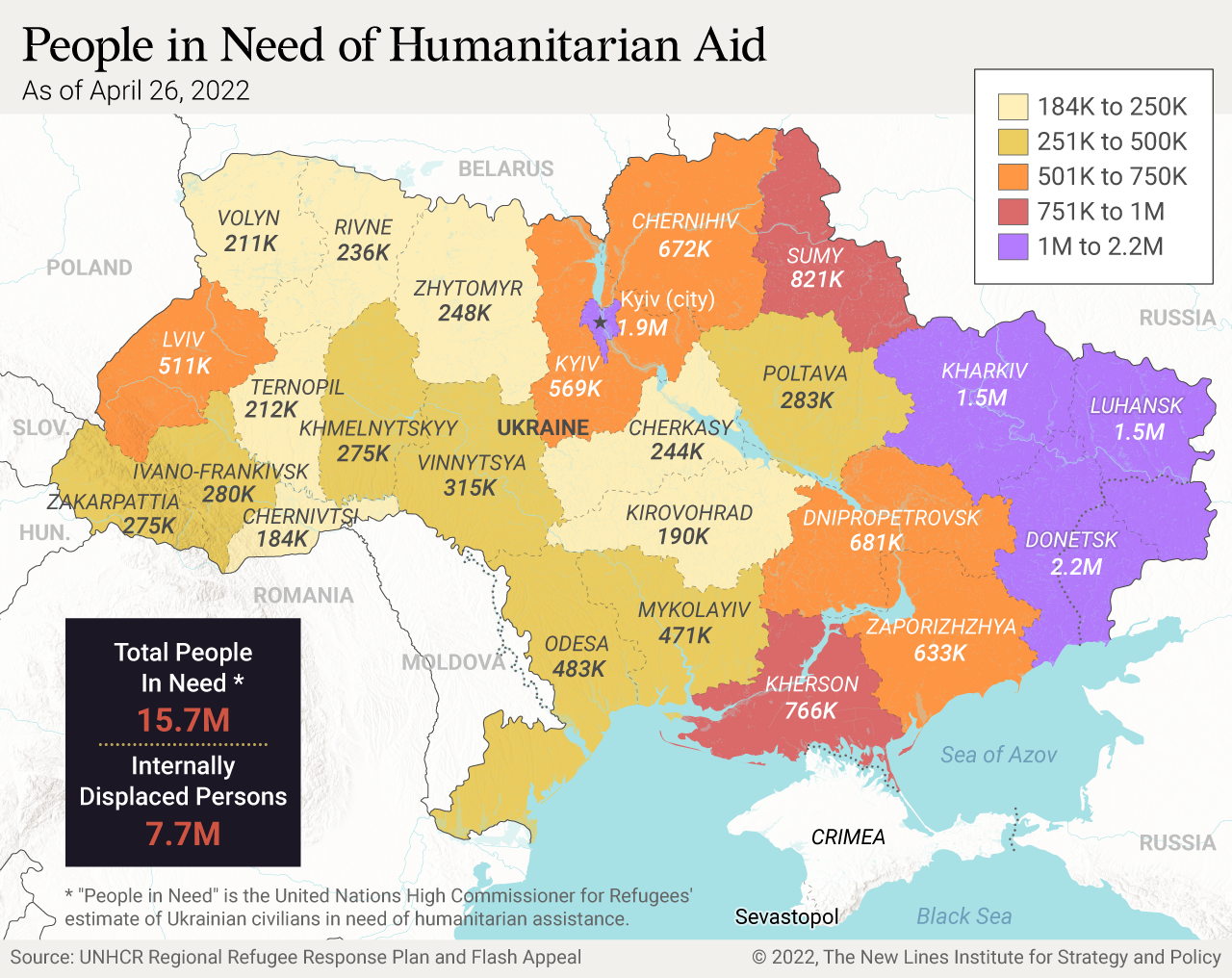

As of May 2, more than 11 million people, one-quarter of Ukraine’s population, have fled their homes due to Russia’s invasion. According to UNHCR figures, more than 5.5 million, mostly women and children, have left their country and become refugees since the invasion began on Feb. 24. More than half of the country’s estimated 7.5 million children have been displaced. Ukrainian men aged 18 to 60 are eligible for military call-up and cannot leave. After just over two months, these numbers are comparable to those of Syria’s decade-long civil war, which has displaced more than 13 million people.

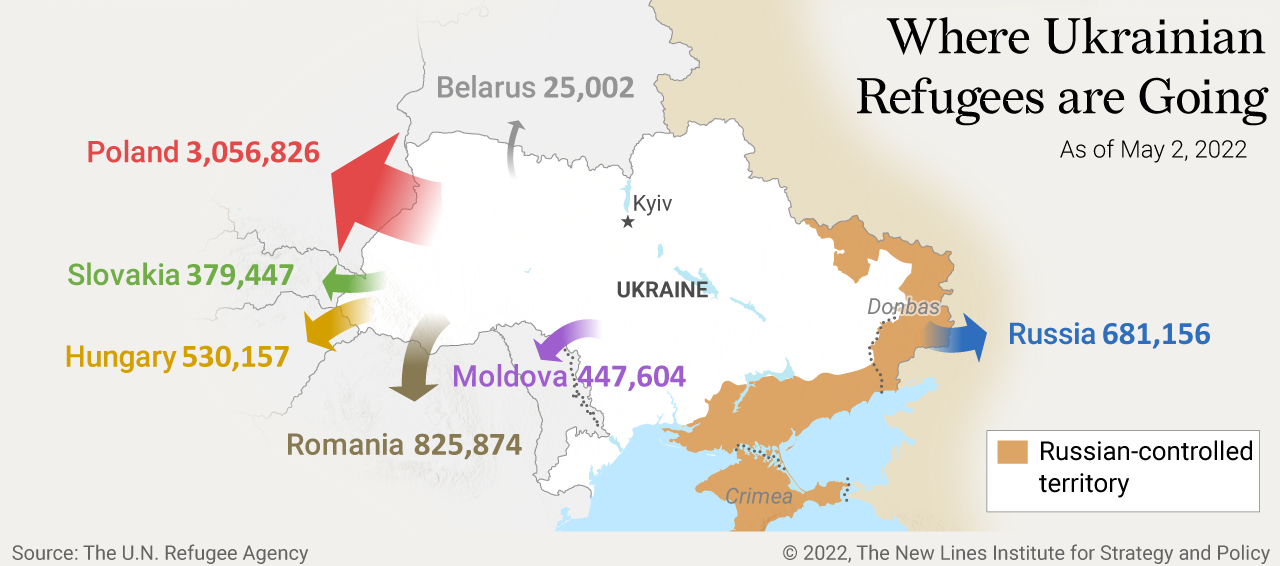

Ukranian refugees are crossing to neighboring countries to the west, such as Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Hungary, and Moldova. Many of these countries are vulnerable to Russian provocation, and some are not equipped to deal with refugee influxes of this size due to economic disparities and lack of legal mechanisms and social services. Eastern Europe serves as a gateway into Europe for migrants from Asia and elsewhere, so many of their facilities are already stretched thin by asylum applications.

Before the Russian invasion, the last instance of major internal displacement in Ukraine began in March 2014 following the Russian Federation’s annexation of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and subsequent war in the Donbas, which resulted in around 1.7 million internally displaced in Ukraine and 1.4 million Ukrainian refugees in Western Europe and Russia. Refugees from the crisis were not warmly received by the European Union, had a comparatively low asylum claim success rate, and were neglected by the media. Without durable solutions, the displacement of these Ukrainians became increasingly protracted. Although clashes had reduced in recent years due to several cease-fire agreements, there were still around 854,000 people internally displaced prior to the Russian invasion, the majority of whom had been displaced during 2014 and 2015. Many may have now been displaced again.

International Response

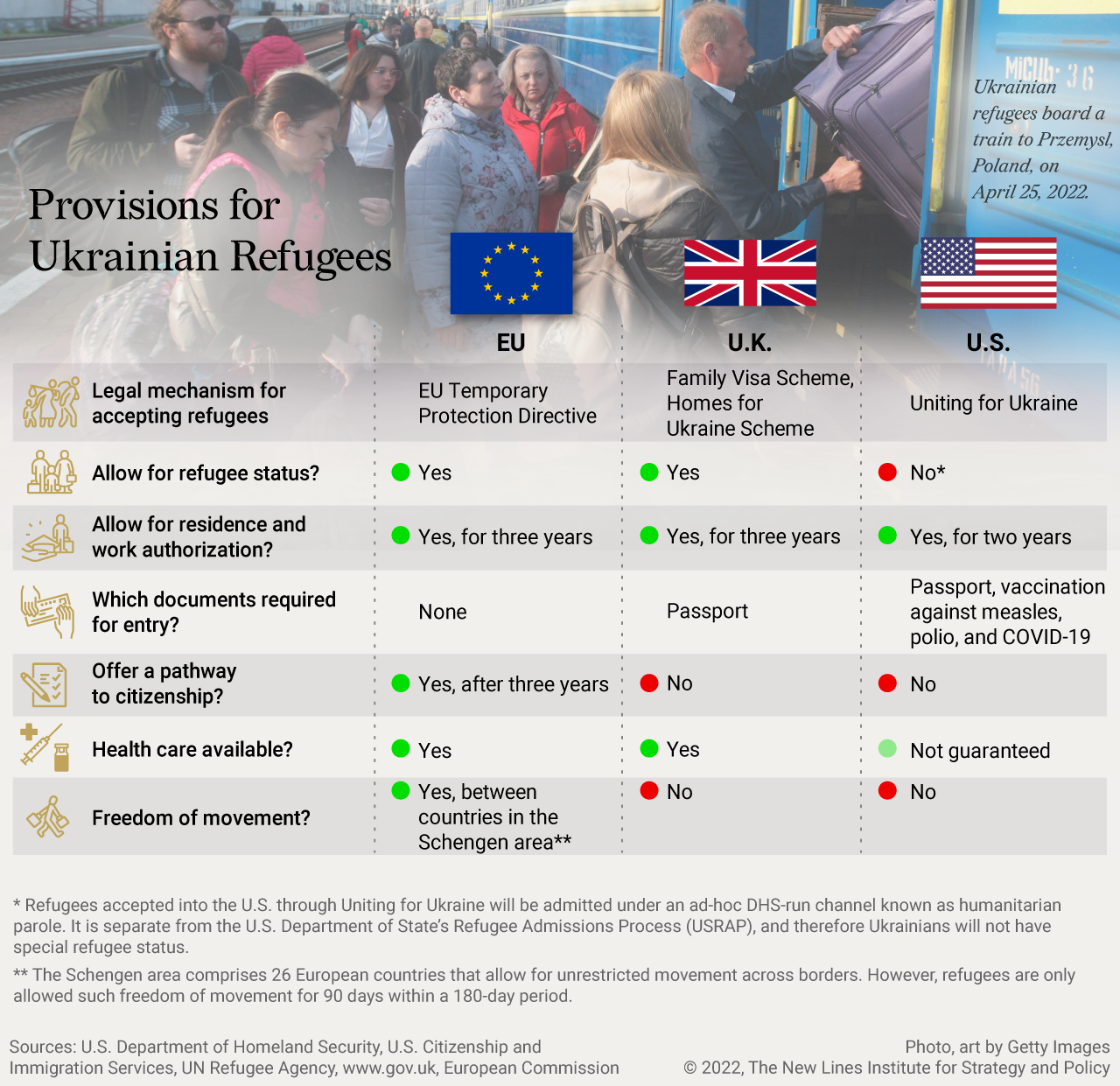

Since the Russian invasion, there has been an outpouring of support for Ukrainian refugees fleeing abroad, particularly from the EU, which quickly granted Ukrainians fleeing the war the right to stay and work throughout the 27-nation bloc for up to three years. The EU also invoked across member states for the first time a 2001 Temporary Protection Directive, which gives refugees the chance to stay, work, and put their children in school automatically – without the delays and bureaucracy of the normal asylum procedure. The U.S. has announced it will take in 100,000 Ukrainian refugees and offer $1 billion in humanitarian aid to European countries housing refugees.

This comes in stark contrast to the EU’s responses to previous migration crises from Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. For example, during the 2015 migrant crisis when more than 1 million Syrians, Afghans, and Iraqis arrived at European shores, or in 2021 when Afghans fled following the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan, the EU’s rhetoric centered on containing refugees outside of the region rather than extending EU protections to them.

Following the increased flow of refugees in 2015, the EU heavily invested in Frontex, its border agency, allowing it to secure its external border with military tools, including armed border guards. The European Commission highlighted a 2015-2016 report from the European Network Against Racism (ENAR) showing that the introduction of new border policies and counterterrorism measures led to ethnic profiling and discriminatory policing of migrants by authorities, as well as racist attacks against migrants, asylum seekers, refugees, and their accommodation in EU member states.

While geographical and cultural proximity partially explain the EU’s response to Ukrainians versus those outside of Europe, its migration and asylum policies have disproportionately penalized Black and brown people. For instance, Denmark, which has some of the toughest anti-immigration legislation in Europe, passed a law that offers Ukrainian refugees expedited residency and work permits, giving them access to the education and health care systems. However, the law comes as Syrian asylum seekers have been waiting for months in Danish deportation centers after the country started revoking their residency permits in 2019.

Though there are evident racist disparities between the treatment of Ukrainians compared with migrants from the Middle East and North Africa, factors like Christianity and whiteness might not offer Ukrainians protection in the long term. As evident in Britain, xenophobic stances towards Poles, Romanians, and Bulgarians persist despite many of them being white. As the numbers of Ukrainians seeking long-term refuge in the EU increase and potentially strain resources, these countries may begin to adopt a more anti-migrant stance. As refugee crises compound one another their impact on anti-immigrant far-right forces in the EU and the response of countries like Denmark and Hungary, with previously hostile immigration stances, will have long-term implications for refugee integration in Europe.

This crisis has shown a shift in the EU’s initial response to forced migration. The question is whether this shift will have long-term effects on the dynamic between EU host countries and displaced persons seeking refuge in them. As with the COVID-19 pandemic, this crisis will likely strain relations within the EU between the “Frugal Four” bloc (Austria, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Sweden) and the rest of the member states, especially as Eastern European countries request increased aid.

Economic Impact

To help refugees settle quickly, as well as to fill their own labor shortages, the European Union has granted Ukrainians who flee the war the right to stay and work for up to three years. Thousands of jobs are being offered exclusively to Ukrainian refugees by on-the-ground recruitment agencies and through a vast network of online job boards that has sprung up across social media. The types of employment available to refugees range from high-level engineering jobs to retail and factory work.

This form of outreach is happening with a speed and scope that is rare for the European Union. Unlike refugees who have flooded Europe from wars in Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan, Ukrainians are being placed on a fast-track protection employment, as governments waive visa requirements and provide almost instant access to labor markets and education.

A motivating factor for anti-immigration rhetoric historically has been the notion that migrants will “steal” jobs from hardworking citizens. However, in countries like Lithuania that have struggled with labor shortages linked to an aging population, a declining birthrate, and the migration of young people elsewhere in Europe in search of well-paying jobs, the influx of Ukrainians is seen as at least a temporary solution to their labor shortage problem.

Ukraine has a skilled work force, with 70 percent of workers holding secondary or higher education degrees, but refugees will need to secure housing, as well as day care and school registration for their children, before they can start working. It is more likely positive impacts on the labor market will not be seen until next year when refugees have been integrated further.

Housing needs to accommodate Ukrainian refugees are increasing on a scale strongly exceeding construction capacity, especially in Poland, where the government has not established camps or other forms of large-scale housing facilities. The Warsaw mayor has indicated the city is at capacity and called for more international financial support to offset the effects of the influx like supply chain disruptions and higher inflation.

Human and Regional Security Risks

The destruction of infrastructure, disruption to public services, and a rapid rise in casualties, make the impact of mass displacement on civilians more severe. For many IDPs who have been in a protracted state of displacement for eight years, needs were already high and were further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Attacks on Health Care

The disruption to services and supplies throughout Ukraine poses an extreme risk to Ukrainians still inside the country with cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, HIV, and tuberculosis, which are among the country’s leading causes of mortality. According to the WHO, displacement, poor shelter, and overcrowded living conditions caused by the conflict are also increasing the risk of diseases such as COVID-19, measles, pneumonia, and polio.

While the WHO has been able to deliver 150 metric tons of medical supplies and establish supply lines from its warehouse in Lviv to many cities, access to many parts of the country remains blocked. A humanitarian convoy to Mariupol couldn’t be dispatched due to the siege. IDPs injured from the war seek refuge in hospitals, which are meant to be classified protection zones during armed conflict, but if these sites are attacked, they are displaced again, this time with more severe injuries.

The WHO has verified 64 Russian attacks on health care centers and hospitals – a war crime under international law – since the start of the war and is in the process of verifying others. The deliberate targeting of health workers and facilities was part of Russia’s strategy during its intervention in the Syrian civil war, and several high-ranking military officials from that conflict are overseeing the invasion of Ukraine. The siege of Mariupol, under the command of Russian Col.-Gen. Mikhail Mizintsev, who led the operation in Syria, has seen the bombing of the city’s maternity hospital, children’s hospital, drama theater, and civilian homes. Gen. Alexander Dvornikov, notoriously known as the “Butcher of Syria” for his command of widespread abuses against the civilian population, was as appointed commander-in-chief of the Russian Ground Forces, indicating Russia will continue to target civilian infrastructure.

Vulnerable Civilians Left Behind

Ukraine’s martial law prohibits men aged between 18 and 60 from leaving the country, which has not only separated families but also impacted men with disabilities, those with sole responsibility for their children, and the elderly. Some men with disabilities and in possession of certain documentation have been allowed to leave the country, but often they have been unable to do so.

Civilians who are trapped in besieged cities like Mariupol have been without food, water, or electricity, and their evacuation has been repeatedly delayed as Russian troops fire upon agreed-upon humanitarian corridors. Most recently, an International Red Cross convoy was forced to turn back after a failed attempt to evacuate Ukrainians trapped in Mariupol.

Furthermore, there have been reports of discrimination and violence by Ukrainian forces toward third-party nationals. People from Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia have said Ukrainian forces and staff have prevented them from boarding trains bound for Poland in the Lviv train station. The International Organization for Migration noted that these reports are due to discrimination on the basis of race, ethnicity, nationality or migration status and encouraged countries receiving refugees to use an inclusive approach when processing refugees.

Forced Migration into Russia

There is limited but growing evidence that some Ukrainian civilians have been forced to relocate to parts of Russia and Russia-controlled areas. The list of claims includes statements from the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), the Mariupol City Council, ambassadors at U.N. Security Council Briefings, as well eyewitnesses who escaped Mariupol, where the forced deportations are reportedly occurring.

The statement issued by the OSCE issued echoed previous reports by Mariupol City Council that Russia’s forces have forcibly deported locals, confiscated their Ukrainian passports, and sent them through filtration camps and then to remote locations in Russia. It also stated that eyewitnesses have reported one of the filtration camps is operating in Dokuchaevsk, in the Donetsk region.

The report cites evidence that Russia has made it difficult and often refused to allow the safe passage of civilians aided by the Ukrainian government or international humanitarian organizations like the IRC from besieged areas. It states that the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) has documented the arbitrary detention and enforced disappearance of 22 local Ukrainian officials in regions under the control of Russia’s military and noted several instances that resembled “hostage-taking.”

News outlets like CNN, BBC, and The Economist have reported on these filtration camps including eyewitness accounts from Ukrainian civilians, although none have been able to independently verify the claims. As accusations continue to come to light, there should be a formal investigation by the OHCHR as forced deportations constitute a war crime under international law.

According to the UNHCR, more than 600,000 Ukrainians have been registered as refugees in Russia since the invasion began. Russian Col.-Gen. Mikhail Mizintsev said that Russia has evacuated more than 550,000 people from “dangerous regions of Ukraine” to Russia, including more than 121,000 people from Mariupol. While not all these Ukrainians were forced to flee Ukraine, it is likely not all are fleeing as voluntarily as Moscow claims.

Policy Recommendations

As fighting intensifies in the Donbas and eastern Ukraine, IDPs may be displaced multiple times in their search for safety. The U.S. can play a critical role by working effectively with its allies and humanitarian partners to ensure there is an international monitoring mechanism for the safe passage of civilians through approved, existing humanitarian corridors from areas under siege. For refugees, if the situation in Ukraine remains highly volatile, they will be forced to resettle in their new communities, prolonging their lives as migrants. Humanitarian aid must be structured beyond its emergency response relief into long-term support for refugees in front-line states like Poland and Romania, in addition to IDPs in protracted situations.

U.S. President Joe Biden has emphasized the importance of the United States being a force multiplier in the world to meet global challenges. The Ukrainian refugee crisis represents a critical moment for Biden to live up to this promise and recommit to the US’s shared goals, values, and responsibilities. While Biden has responded by granting up to 100,000 Ukrainians fleeing the conflict temporary status in the U.S., most Ukrainian refugees will be looking for a safe passage into and resettlement in Europe due to geographical proximity. Even as Moscow and the West remain far apart in terms of the broader conflict, the U.S. should continue to negotiate items on the humanitarian agenda with Russia, including keeping humanitarian corridors open and accessible. It is critical for the U.S. to be a proactive influence in encouraging its partners in Europe to manage the ongoing crisis effectively.

Beyond the $1 billion in aid that the U.S. has provided to assist EU countries with their emergency responses to the crisis, the U.S. can do more to leverage its relationship with its partners to lead from behind on this issue as it becomes more protracted. As the U.S. is overall less affected by the refugee crisis than their European allies, it can act as a positive convener for EU member states to have structured dialogue to discuss how Washington can continue to support Ukrainian refugees and the countries hosting them through diplomatic efforts, strategic burden-sharing, and the coordination of donations – from foreign assistance to multilateral institutions.

As the refugee crisis is evolving, it will have secondary and tertiary effects in other countries and humanitarian crises around the world. To support Europe, and especially Eastern Europe, the U.S. must work to ensure all humanitarian assistance remains flexible to meet evolving needs. To do this successfully, it is essential for the U.S. to apply pressure on its allies and partners to guarantee equitable access and delivery of assistance not only to refugee-hosting countries but also to crisis-affected populations in Ukraine. In addition, the U.S. can leverage its role with partners at international forums on security cooperation to encourage an ongoing, coordinated safe passage of vulnerable displaced persons to areas not under Russian control. Regardless of whether those displaced are IDPs or refugees, it will be necessary to ensure adequate infrastructure to support their psycho-social and economic adjustment as well as their health and safety.

Alice Hickson is an Analyst for the Power Vacuums program in the Human Security unit at the New Lines Institute. She studied in Jordan where she conducted independent research for her thesis on Palestinian refugees and the right of return. Alice holds a Bachelor of Arts in International Relations and Middle Eastern Studies from Tufts University. She tweets at @_AliceHickson.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not an official policy or position of the New Lines Institute.