Why U.S.-China Relations Need a Gender Analysis

The threat that authoritarian countries, particularly China, pose to the rules-based international order is one of the biggest foreign policy challenges the United States currently faces. For Washington to successfully engage with China, it must apply a gender lens to its relations, especially if the U.S. wants to push back against the ease with which China appears to be exporting its model of governance to the rest of the world.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) relies on patriarchal authoritarianism, as detailed by Dr. Leta Hong Fincher in her book Betraying Big Brother, to maintain its control, working to reinforce “traditional” masculine norms and going so far as to say that “feminized” men would “inevitably endanger the survival and development of the Chinese nation.” By capitalizing on society’s male surplus, or what many refer to as “bare branches,” to improve force readiness, satiate the growing desire for private security companies, profit off of gains from its Belt and Road initiative (BRI), and turn a blind eye to bride trafficking into the country from across the region, President Xi Jinping and the CCP are effectively using gender geostrategically.

The U.S., however, has consistently ignored a strategic gender analysis when it comes to navigating its policies toward China. This may be in part because policymakers too often assume gender is not important or only important as a function of “soft power” in statecraft and great-power competition, despite growing support for a feminist foreign policy. To counter China, the U.S. should weave a gender analysis throughout its Chinese-oriented national security policies, increase funding for the Women, Peace, and Security Agenda in the Department of Defense, and highlight America’s diverse leadership, which includes women in many key foreign policy positions.

The structure of any nation relies on the construction of gender norms, notions of “manhood” and “womanhood,” and the nation’s reproduction of its people through citizenship and culture. This is particularly true for authoritarian states, which are directly linked to upholding traditional gender roles and attitudes and holding negative attitudes toward feminists and feminism. In China, this correlates to traditional gender norms around male-oriented social dominance and gender essentialism. Authoritarian states also wield traditional gender norms to support a sense of in-group and out-group mentality that allows autocrats to exploit traditional gender hierarchies and decry feminists as enemies in an effort to maintain their own power. While there is growing recognition in the foreign policy community of the ways in which authoritarian states, primarily Russia, are using gender to further their domestic and foreign agendas, the same nuanced understanding does not exist with respect to China.

There remains a strong need for the U.S. to confront China’s authoritarian (and potentially fascist) model of governance and address the ways in which China is utilizing its understanding of gender to advance its global agenda, often to the detriment of U.S. foreign policy goals.

Gender & China

Most discussions on gender and China fall too easily into stereotypes, Western assumptions, and an outdated analysis of the one-child policy. For instance, claims are often repeated of the more than 30 million missing girls in China using racist stories of families killing their daughters. While we will not underscore the impact the one-child policy had on families across China, many of the Western claims of the 30 million missing girls killed or aborted are inflated. One of the researchers who first began publishing on “finding” the missing girls highlights the potential impact this had on diplomatic relations between the West and China, where negative assumptions were made about China’s treatment of women. The reality is that nearly 10 million of these women were unregistered when they were born in the 1980s and 1990s, but “re-appeared” in society later in life only to discover that they lacked access to public services, which increased their vulnerability.

China-related foreign policy needs to be more nuanced and use culturally specific gendered analyses as opposed to old, reductive arguments that equate missing women with femicide and more young men with violence. The stories of the missing girls are paired with outsized fears of the “bare branches” of Chinese society: young, unmarried men who are unable to progress into all the traditional roles expected of them, leading, in theory, to instability and insecurity. Though there are large cohorts of men who are unmarried and lack economic prospects, many of the fears that this will lead to instability are largely unfounded, according to empirical data. A more nuanced look finds male youths’ susceptibility to violence is in reality due to socio-cultural factors and their experiences of patriarchal, male-dominated marginalization and not just because of skewed gender ratios.

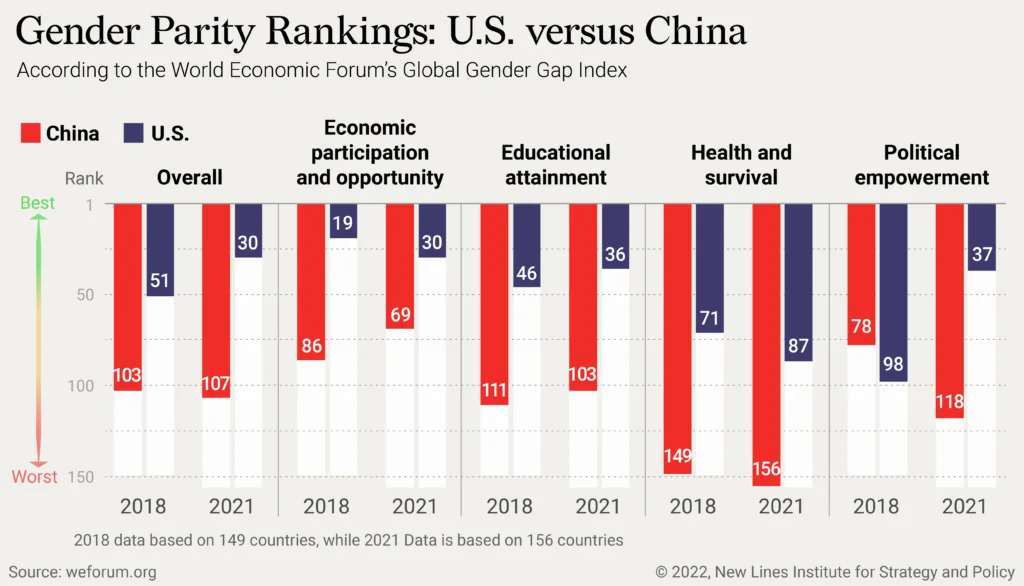

The CCP historically has understood that there needs to be a distinct difference in the domestic and global discussions around gender equality, feminism, and women’s liberation. One of the most notable turning points in the global discussion around women’s rights and gender equality took place in Beijing at the 1995 Fourth Conference on Women that spurred a worldwide discussion on women’s rights and ultimately led to the passage of the Women, Peace, and Security Agenda in 2000. In the years since, however, China’s commitment to gender equality has stagnated, and the participation of Chinese women in the labor force has dropped compared to the rest of the world. There are no female members of the elite Politburo in the CCP, and their participation in the National Congress of the CCP remains staggeringly low. The Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace, and Security ranks China 89th out of 170 countries in their 2021 Women, Peace, and Security Index, which tracks sustainable peace through inclusion, justice, and security for women.

The treatment of Chinese women internally is at odds with how Xi and the CCP performatively support a global women’s movement when it suits their needs, such as when China in 2015 co-hosted the 20th anniversary of Beijing’s World Conference on Women with a U.N. summit on women’s rights in New York. Concurrent with this public validation of women’s rights, Xi was quietly arresting the leaders of a feminist movement in China, the “Feminist Five,” for planning to host an event commemorating International Women’s Day with stickers about sexual harassment. Despite their ultimate release, feminist activists across China have either left the country or continued to be arrested because feminist activism is at odds with the patriarchal authoritarianism of the CCP regime and ultimately Xi’s global agenda.

This treatment of women continues to plague activists in China. It is readily apparent in the way China has used the Olympics to project a carefully prescribed public image through strategic propaganda such as having a Uyghur woman light the Olympic torch and the very public interview where tennis star Peng Shuai denied having accused a CCP member of rape and reassured a reporter that she remains “very free.” In this interview Peng Shuai also announced her retirement from tennis, ending her long career as one of China’s most famous athletes. Some Chinese women’s rights activists have since acknowledge that Peng Shuai should be allowed to be safe in whatever way she can, implying that speaking out against the CCP was potentially dangerous for her and retracting her comments was integral to her continued safety and security. Being an outspoken feminist and critic of the CCP remains a dangerous position in China.

The Belt and Road Initiative and the Uyghur Genocide

China has the potential to be a force for empowering women globally through its investment and development projects, which would be one opportunity to align China with the U.S. in a cooperative engagement of international importance. Instead, however, China chooses to reinforce patriarchal authoritarian systems globally through its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the centerpiece of the CCP’s foreign policy and Xi’s signature global infrastructure development. After nine years of building railways, power plants, pipelines, and more, the main beneficiaries of BRI are largely men.

While this could be a product of the patriarchal systems of power in the countries in which China is investing, it is also certainly because the BRI has no gender-specific aims despite the fact that China has several commitments under international law to promote gender equality and women’s rights. Instead, the CCP often wields the BRI as a tool to promote China’s model of high-tech fascist governance. At the 19th Party Congress in 2017, Xi said that China’s model of “socialism with Chinese characteristics” provides “a new option for other countries and nations who want to speed up their development while preserving their independence.” The BRI’s unspoken purpose beyond development projects is to share with its partners, especially developing countries indebted to China, an alternative to the U.S.-led liberal world order.

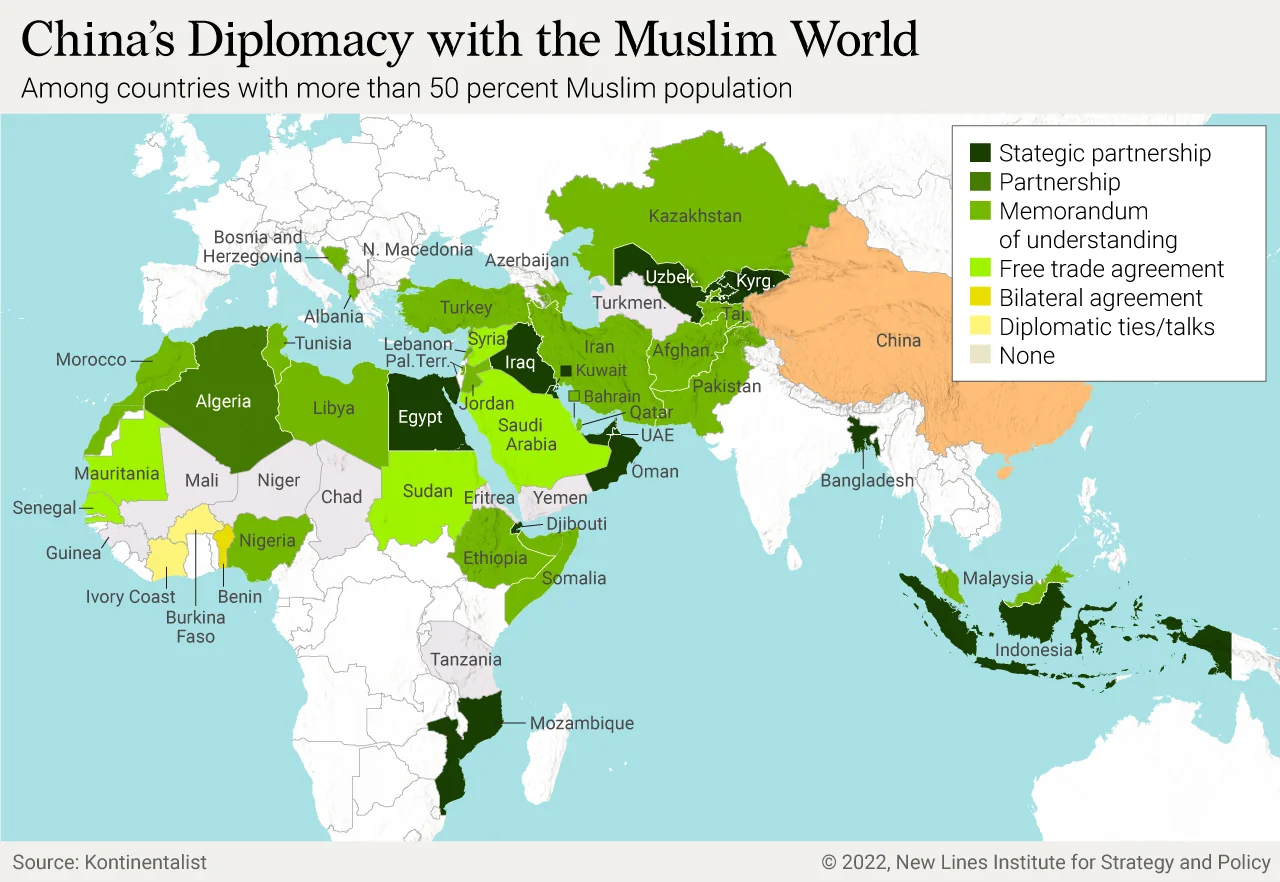

Beyond this, China also uses the BRI to silence foreign critics of its campaign of genocide against the Uyghurs in Xinjiang. In 2019, 37 country representatives, including from Muslim-majority countries like Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, and Sudan, praised China for its human rights record and defended the CCP’s actions in Xinjiang as “counterterrorism” measures. Notably, these countries receive huge benefits from BRI and are beholden to Chinese investments and loans.

In addition to its lack of gendered policies and use by China as a geopolitical instrument, the BRI has come under fire for its problematic labor practices. Instead of hiring workers from host countries, promoting employment, and creating opportunities for local skill-building, Chinese firms often rely on imported Chinese labor for BRI projects, in part to minimize labor costs but also because these laborers include large numbers of unmarried and economically disadvantaged men who are vulnerable to predatory practices like forced labor and human trafficking.

In June 2021, the U.S. and other G7 countries launched the Build Back Better World (B3W) Partnership, a direct response to the BRI, to narrow the infrastructure gap in the developing world. One of the four main areas of focus for B3W is gender equity and equality – precisely what the BRI is missing. B3W shows how the U.S. can use, and is using, gender to its strategic advantage in its competition with China. Though China may be ignoring gender in its signature foreign policy, the CCP certainly has been using its understandings of gender to carry out domestic policies, including the aforementioned Uyghur genocide.

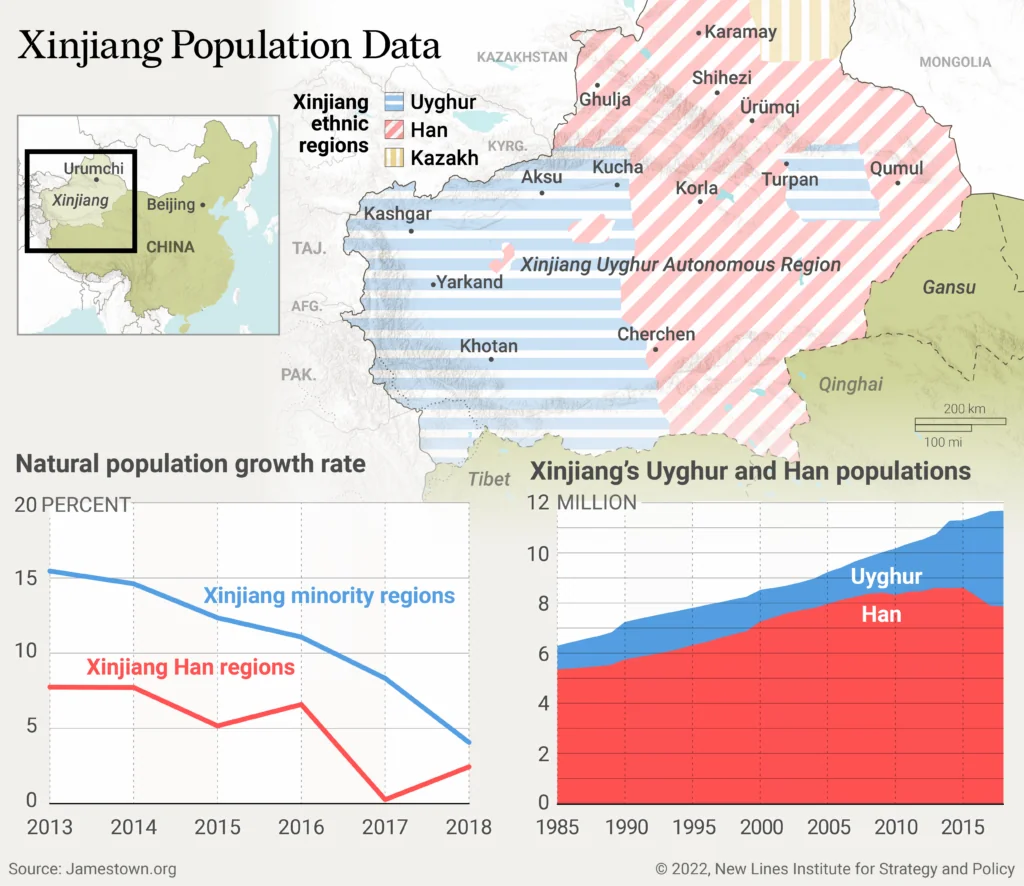

A hallmark of the Uyghur genocide has been the coercive birth prevention programs both inside and outside the camps. In 2019 alone, these programs received $37 million to pursue the goal of decreasing birth rates in Xinjiang – and they succeeded. Birth rates dropped 24% compared to 4.2% nationwide. Beyond this, the CCP has targeted Uyghur women, men, and children in various, specific ways relating to their gender. For example, Chinese government propaganda is increasingly sexualizing Uyghur women in order to entice Han men to marry them. Several incentives for these interethnic marriages exist, including cash rewards, housing, and free education for their children, who will be considered Han Chinese, not Uyghur, in an effort to erase their identity and break their lineage. The CPP is engaging in a time-tested imperialist policy of “breeding out” Uyghur identity, a practice that empires have used against certain populations throughout history.

The Uyghur genocide does not just target Uyghur women; the CCP has sought to prosecute high-level Uyghur men, sentencing them to long prison sentences and labor camps. It is imperative that the U.S. remains committed to contextualizing the genocide as part of a broader movement by the CCP to utilize traditional gender norms in order to maintain power and control throughout the state.

Though historically U.S. State Department lawyers have been slow to determine genocide (for a variety of complex reasons) and don’t appear to view the crime of genocide through a gendered lens, the United States was the first country in the world to officially determine that China is in breach of the 1948 Genocide Convention and has been a leading voice on the global stage over the past year. Among its attempts to call out China for its intense human rights abuses, the U.S. has implemented targeted sanctions against CCP members complicit in the Uyghur genocide, passed the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act, and staged a diplomatic boycott of the Beijing Winter Olympics.

The Women, Peace, and Security Agenda

The Women, Peace, and Security Agenda (WPS) is a global agenda based on a series of U.N. Security Council Resolutions that broadly attempt to address the inequitable experiences of women in conflict and support and promote their role in peace movements and negotiations. The discrepancies between how China and the United States have engaged with the broader WPS agenda highlight a real difference in how these superpowers potentially interact with their respective allies and security partners. There is a real opportunity here for the United States to have a competitive edge over China in its increasingly fraught strategic competition and for the Biden administration to use its National Strategy on WPS to shore up support with America’s partners in China’s sphere of influence.

In 2019, the United States released its National Strategy on Women, Peace, and Security as a follow up to the 2017 legislation that codified it into law. This strategy largely matches the global WPS agenda as it relates to U.S. foreign policy. However, support for the WPS agenda in the Security Council is not necessarily a guarantee despite widespread acceptance of the agenda globally. China and Russia in particular have fomented backlash against some aspects of the WPS agenda, actively worked to weaken the language around sexual violence in recent resolutions, and abstained on a vote to pass Resolution 2493. China also has yet to adopt a National Action Plan and has instead developed its own initiatives around women in conflict by sending female peacekeepers to conflict zones and hosting workshops on enhancing the WPS agenda. Nevertheless, just because China does not have a National Action Plan does not mean the CCP is not engaging with the agenda.

The U.S. and a Chinese Sphere of Influence

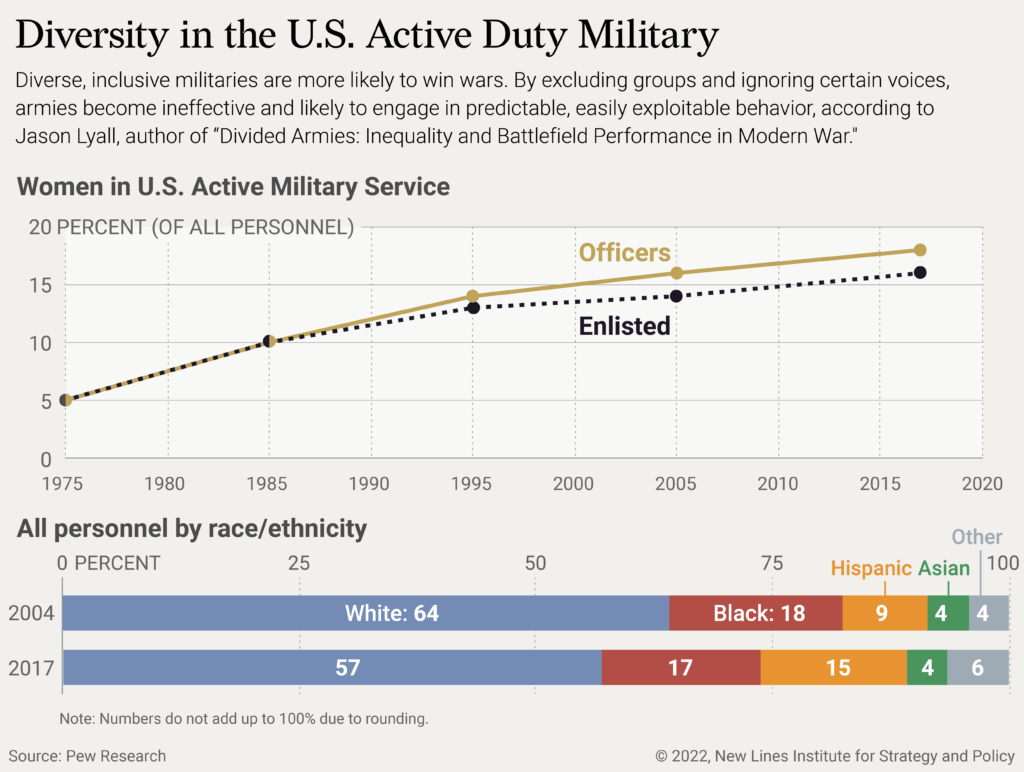

There is also a large disparity in how China and the U.S. treat women in the military. Women make up only 4.5% of the Chinese military, and the same year that China first started training female fighter pilots, they also instituted a talent segment for female People’s Liberation Army soldiers and often put them in roles that are more focused on publicity and administrative work than on any real combat or training. Instead of opening up the military to be a more inclusive space that embraces diversity and a variety of strengths and skills that make modern militaries more effective, China has instead sought to force young boys to be more masculine and to silo young women into support positions like administration or communication.

By increasing its commitment to the broader global WPS agenda and further integrating it into Security Force Assistance operations in the Pacific, the U.S. can exploit an advantage over China, realizing the significant and crucial role that 50% of the population plays in maintaining global peace and security. Regarding long-term gains, training and equipping more than 50% of partners’ capacity in the Pacific can reignite a commitment to the liberal norms and ideals that President Joe Biden has made a key part of his foreign policy. The United States has started to integrate increasing women’s meaningful participation in the security sector into Security Force Assistance programming. One of the three primary objectives for the Department of Defense’s WPS plan is “women in partner nations meaningfully participate and serve at all ranks and in all occupations in defense and security sectors.” This should be an integral component of how the United States plans to posture in the Pacific as it fights to remain a reliable partner and guarantor of peace and stability in the region.

Forecast

The CCP is brazenly committing a genocide, even during the Winter Olympics; China is increasingly engaging in targeted military activity near Taiwan; and while Xi extolls the virtues of women’s rights internationally, the government locks away feminist activists and discredits those who dare to dissent like Peng Shuai. The U.S. must understand China better as an adversary and act more strategically in its foreign policy in order to successfully address the challenge. China has changed the rules of the game by not following any rules at all, and if the U.S. continues to act like this is not the case, China will continue to export its model of high-tech authoritarianism, unopposed, in direct conflict with U.S. interests. Continuing the status quo for America’s China policies is unproductive, and the U.S. will miss out on significant opportunities to counter Chinese influence in the South China Sea and South Pacific as well as the chance to counter Chinese influence in developing countries.

Recommendations

It is imperative that the U.S. start incorporating a gender perspective into all issues of national security; the creation of the White House Gender Policy Council was an important first step, but taking a gendered approach throughout foreign policy and national security decision making should be a critical priority. The U.S should demonstrate a more informed approach and a more gender-balanced society as a counter to authoritarian patriarchy. The U.S. does not need to position China as a bogeyman but instead should be focused on shoring up domestic and international policies that promote gender equality that can act as a counterbalance to rising authoritarianism around the world.

- A gender analysis should be threaded throughout Chinese-oriented national security policies. A positive example of this is the inclusion of gender and women’s equality into the B3W Partnership launched by Biden and the G7 leaders. This agenda is important as a mechanism to incorporate gender equality into bold, multifaceted foreign policy plans focused on human infrastructure such as global welfare, good governance systems, and strengthening partnerships – all of which are made stronger with a gender analysis.

- The U.S. should increase support and funding for the WPS agenda in the Department of Defense as a way to counter the rising threat of global authoritarianism, populism, and nationalism in China and throughout the South Pacific. By ensuring that the WPS agenda continues to be funded at increasing levels in future National Defense Authorization Acts, ensuring that there are WPS components in global security cooperation partnerships, and working to support women’s empowerment efforts in the South Pacific, the U.S. can continue to utilize gender and its commitment to the WPS agenda as a critical edge.

- The Biden administration must continue reinforcing its efforts to increase women’s political leadership both domestically and abroad. The Biden administration promised diverse leadership and has so far delivered across his cabinet and numerous other high-profile positions, such as Vice President Kamala Harris, USAID Administrator Samantha Power, and U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Linda Thomas-Greenfield. While representative leadership does not necessarily equate progressive gender-nuanced policies, it is a stark comparison to China’s completely male-dominated Politburo and the overwhelmingly male elite CCP circles. In addition to domestic efforts to increase women’s political leadership at the 2021 Summit for Democracy, the Biden administration announced a pledge focused on Advancing Gender Equity and Equality for Representative Societies, which seeks “to strengthen women-led civil society organizations, tackle entrenched barriers to women’s political and economic participation, and foster a more inclusive environment for women in politics.” This is an important component of the U.S.’ global foreign policy agenda and shows that the Biden administration is aware of the importance of female leadership in the face of authoritarian governments aggressively working against women’s political power.

- Maintaining and growing America’s foreign policy to reflect American values is an important tool in the U.S.’ soft-power arsenal to counter authoritarian states like China. American domestic policy cannot backslide on gender equality and women’s rights. The U.S. must remain steadfast in its commitment to ensuring the equal protection of women under the law, protecting abortion access, and other markers of gender equality where the U.S. is faltering that have a direct correlation to democratic backsliding. Women’s empowerment and gender equality are often framed as the results of democratization and development, when in fact women’s rights and women’s movements are precursors to democracy; a healthy democracy cannot function without gender equality. Autocrats like Xi understand this, and so they fear the gains that women have made and continue to push for in their countries. Instead of allowing Xi to make inroads minimizing the importance and credibility of the international liberal world order, which has sought to promote gender equity, the U.S. should take this opportunity to showcase the work the Biden administration has made with respect to gender equity.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not an official policy or position of New Lines Institute.