With a new leader at the helm, al Qaeda’s North African branch is likely to continue to work with local jihadist groups and continue to pose a challenge to regional security.

In late November, more than five months after al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) leader Abdelmalek Droukdel died in a raid by French forces, the group announced that Abu Ubaydah Yusuf al-Annabi would take over as the new emir.

Al-Annabi is the mastermind behind AQIM’s recent evolution. While al Qaeda does not recognize national borders or flags, AQIM recently has increasingly involved itself in local Algerian and Malian dynamics, with leaders appearing in front of national flags and publicly endorsing local causes. al-Annabi’s rise to lead the militant group likely will mean a continuation of the flexibility that has contributed to its resurgence – not just in Algeria and Mali but also increasingly elsewhere in West Africa.

AQIM’s Announcement

The announcement of al-Annabi’s ascension came in an Al-Andalus compilation of mostly old footage. The video begins with a lengthy eulogy for Droukdel and three jihadists who died alongside him, including the media boss of Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM), the group that united several jihadist factions under the banner of AQIM to operate in Mali and the Sahel in 2017.

The video goes on to describe Droukdel’s final days: “Abu Moussaab died among his brothers and soldiers of JNIM after sharing with them times of peace and times of war,” This indication of the amount of time Droukdel had been spending in northern Mali, away from his Algerian sanctuary, emphasizes his personal involvement in local dynamics there.

The video also makes specific mention of the jihadists killed in the same raid as Droukdel. Abu Abdel Karim, an ethnic Dogon from central Mali, was a known preacher and religious scholar. The video’s mention of the Dogon shows the recruitment reach of jihadist groups in the Sahel, which now goes beyond the ethnic Arab, Tuareg, and Fulani communities that mostly make up JNIM. AQIM’s recruitment into these groups gives it a wider geographical scope that can reach into neighboring countries.

After this lengthy introduction, the video takes no more than 45 seconds to announce al-Annabi as the new emir before moving on to further praise of Droukdel. The brief announcement has been subject to some misinterpretation, with observers assuming the brevity of the announcement to indicate the weakness or irrelevance of the new leader. But this ignores previous jihadist eulogy videos, which have tended to be long and florid, especially when contrasted with leadership announcements, which have been brief and sober.

The sole survivor of the French raid is the driver, Boubacar Diallo (aka Abu Bakr al-Fulani), whose name was on the handwritten list of the prisoners whom JNIM demanded be released in return for the liberation of hostages Soumaïla Cissé and Sophie Pétronin. The list indicates that Diallo was in Malian intelligence services’ custody. (The author has confirmed that he was released.) That Diallo was driving the AQIM leader and JNIM’s media boss in the same car, and that he was on JNIM’s prisoner swap list, emphasizes the tight organizational and subordination links between JNIM and AQIM. Moreover, according to French intelligence, Droukdel held a “strategic meeting” with JNIM leaders Iyad Ag Ghali and Hamadoun Kouffa in February 2020 in central Mali. French intelligence says that a source shot video of the meeting, but the footage also could have been recovered by French special operations forces after the killing of Droukdel and the head of JNIM’s media office.

Al-Annabi’s ascension was indeed carefully considered. The author asked an AQIM source shortly after Droukdel’s death why a successor had not been named, and the answer was brief but meaningful: “These matters take time, to rearrange internal matters and to establish contact with other al Qaeda affiliates.” We can thus assume that protocol was followed with respect to Droukdel’s position as the longest-lasting head of an al Qaeda branch.

Al-Annabi’s Background

Al-Annabi, whose birth name is Yazid M’barek, was born in 1969 in Annaba, a coastal town in eastern Algeria, according to his Interpol file. Though he has been designated as a terrorist by U.S. and European authorities since 2015, AQIM says he “joined jihad” in 1992 or 1993.

It is improbable that he participated in the Afghan jihad or visited Afghanistan or Pakistan in those early years. Instead, he likely joined one of the many small, local groups active in his native region that orbited around the Groupe Islamique Armé (GIA), which claimed responsibility for several attacks, including hijacking an Air France commercial flight in 1994 and bombing the Saint Michel train station in Paris in 1995.

The GIA also was one of the most active factions during the “Black Decade” – the brutal, 10-year-long civil war between the Algerian government and an Islamist insurgency. That war came to an end as militant factions cut deals with Algerian authorities, culminating in a 1999 amnesty law. However, some factions chose to “clear the ranks” and continue fighting, resulting in the Groupe Salafiste pour la Prédication et le Combat (Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat) splintering off from the GIA in 1998.

Less than a decade later, this group would vow allegiance to al Qaeda and rebrand itself as al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb. The man who made that 2007 announcement was al-Annabi. Three years later, in 2010, al-Annabi was heading the Council of Notables, the most senior assembly that answers to and advises AQIM leadership. And three years after that, he was calling for jihad against France after French military involvement in northern Mali.

The Future of AQIM Under Al-Annabi

In early 2019, the author sent al-Annabi 12 questions, which he answered in a 52-minute-long audio compilation. It is a rare occasion for a senior al Qaeda representative to answer questions from Western media, indicating that al-Annabi is portraying himself as more of a political figure than an operational commander.

The first two questions were about the Algerian protest movement that began in February 2019, and al-Annabi dedicated more than half of the time answering them. He said the protests are “a natural continuation of the military struggle of AQIM,” which is in accordance with al Qaeda’s support for popular uprisings in the Arab world, such as Egypt and Tunisia. AQIM itself has halted operations in Algeria since the protests began, “to avoid undermining the uprising.”

Significantly, the first AQIM statement under al-Annabi, issued Jan. 17, stressed “the need to pursue peaceful jihad, as for popular demonstrations and civil activities, and military jihad.” According to an AQIM source, “For the time being, AQIM is not calling to resume military actions against the Algerian establishment. Otherwise it would have been clearly written in the statement.”

Al-Annabi likely strongly influenced Droukdel regarding AQIM’s moves in the Sahel, especially in the group’s 2012 directives to spare locals in northern Mali a brutal application of sharia. This stance led al Qaeda’s central leadership to sometimes criticize Droukdel as being too compromising.

But the group’s strategy of entrenching itself in local Malian politics appears to have borne fruit, exemplified by the ascension of Ag Ghali to head JNIM in 2017. Before becoming a jihadist, Ag Ghali was a respected political figure and Tuareg independence advocate in northern Mali. He has inspired respect among locals who see him as one of them, and his presence has helped JNIM (and thus AQIM) entrench itself in local Malian dynamics and gain the upper hand in its ongoing conflict against Islamic State militants in the region. (In this context, there had been speculation that Ag Ghali would take over AQIM after Droukdel’s death, but the group understands the importance of JNIM and of having a local actor at its head.)

In his answers to the author’s questions, al-Annabi gave insight into the dynamics between JNIM and AQIM: “JNIM is a non-dissociable part of AQIM, which in its turn is an non-dissociable part of al-Qaeda central. … Regarding the geographical reality and the military pressure on its leaders and commanders, al Qaeda had to adapt with flexible command and control, therefore giving general and strategic guidelines, and then tactically it is up to each branch to reach toward achieving those guidelines depending on their realities. … AQIM follows the same process of leadership regarding its activity in different African countries.” This can be seen at an operational level – in fact, al-Annabi consulted with JNIM before sending the answers to the author’s questions concerning them, showing a clear consultation process at the leadership level.

Al-Annabi said that his group’s activities in Mali are “a fight [through JNIM] against France and its local and regional allies. Therefore, they are legitimate targets in their countries or in our countries.” He said AQIM would avoid neutral parties: “Our objectives are clear, fighting intruders and occupiers are legitimate in heavenly and earthly laws, so those who stay neutral will be spared.” This statement is an interesting contrast from al Qaeda itself, whose leader Ayman al-Zawahiri in 2017 famously called for “jihad from Abidjan in Ivory Coast, to Ouagadougou in Burkina Faso and the Atlas in Morocco and Mauritania.” One example of this is Mauritania, which kept open channels with AQIM and in return has not been attacked by AQIM since February 2011 despite being part of the G5 Sahel. On the other hand, Burkina Faso had been targeted and lost control of its northern border after the collapse of similar channels. Like Mali, Burkina Faso is now open for negotiations with jihadist factions.

JNIM/AQIM as a Political Threat

Since mid-2020, French forces have shifted their focus in Mali from targeting the Islamic State to targeting JNIM. Droukdel’s death is the highest-profile example, and it was followed by the killing of JNIM official Ba Ag Moussa, a Tuareg figure and Ag Ghali’s lieutenant, in November.

The French campaign has weakened JNIM’s grip on Mali’s border region with Burkina Faso and Niger and prompted an Islamic State “comeback” offensive that resulted in the death of a JNIM field commander and led to a bloody confrontation between the militant groups in December. JNIM prevailed for the second time in that conflict, but a combination of pressure from Islamic State and French forces have left its manpower depleted.

The entrenchment of JNIM (and therefore AQIM) in local Malian dynamics is part of France’s calculus for stepping up its targeting of the groups. Locals caught in the middle of the conflict between the Islamic State and JNIM are increasingly being forced to choose a side between local actors, all of which are committing human rights abuses. The Islamic State lacks significant local acceptance or political experience, while JNIM’s continued presence and the balance of fear it has imposed with government forces, militias, and now the Islamic State in central Mali has made it a more palatable choice. The French strategy of seeking out high-value targets has contributed to disruptions in negotiations between the Islamic State and JNIM, contributing to the inflammation of the war between militant groups in the Sahel.

The strategy also gives Malian authorities an advantage at the negotiating table, though the killing of local jihadist figures by French forces also could undermine the government’s authority in the eyes of local populations. The growing influence of JNIM and AQIM in Mali has been the cause of France’s renewed efforts, but the French strategy could put its forces more at odds with locals in northern Mali who prefer JNIM to the Islamic State. Added to the latest liberations of jihadists from Malian prisons and ransom money dispatched on operatives, it could explain sustained logistics and manpower for recent attacks on French forces in the Sahel that killed five and wounded six military personnel between Dec. 28 and Jan. 2, as well as the shooting incidents targeting French patrols in Kidal. The French military and officials have maintained that France will not negotiate with terrorists, but they recently indicated they would not obstruct negotiations when led by local parties.

As JNIM is evaluated as a sustained, enduring political and security threat, the Islamic State is being considered a sole security threat lacking political experience, acceptance among locals, and steady logistics across the Sahel region. This could be slowly changing in Niger, where some border-area communities are seeking the Islamic State’s help with local problems, including some within the same community, leading to bloody “conflict resolution.”

Conclusion

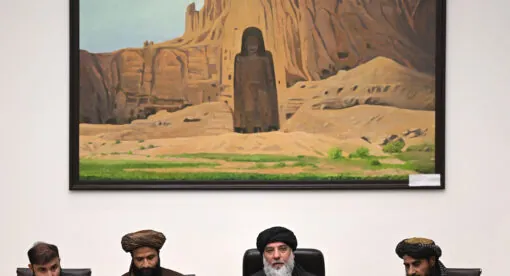

Al-Annabi’s rise to lead AQIM is an affirmation of its efforts to entrench itself locally, with leaders giving speeches with national flags in the background – a rarity, given that AQIM does not recognize national flags or borders – and publicly endorsing local causes. This is a clear effort on the part of the group to test a strategy of addressing Muslims in Mali, and it appears to be working: Today, a majority of Malians approve of talks with JNIM. The group declared Jan. 14 that its confrontation with France is limited to Mali and the Sahel region, noting that “neither before nor after” French intervention in Mali has a Malian attacked France on its soil and pressuring the French public to ask for the withdrawal of French forces, saying that the group never tried to change the way France is governed or the French way of life.

AQIM’s willingness to overlook personal and ethnic grievances to coalesce several distinct local groups under the JNIM banner has given it flexibility and resistance to military pressure, and the strategy has garnered praise from al Qaeda central – the same leadership that criticized Droukdel a decade earlier for being too compromising. We are witnessing a shift away from never-ending battles toward foreseeable political objectives in order to avoid repeating failed governing experiences in Somalia, Yemen, or even Syria. As the group shifted its focus from Algeria in order to survive, it also began to expand and can now be seen as a player in Western Africa. This shift happened under Droukdel with al-Annabi’s influence; it likely will continue now that al-Annabi is AQIM’s leader.

Wassim Nasr is a journalist with France24 and a jihadism expert. Nasr is the author of Etat islamique, le fait accompli (Plon) 2016. He is also a consultant for Terror Studios (2016) International Emmy Awards (2017) nominated documentary. Follow him at @SimNasr.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not an official policy or position of the Newlines Institute.