This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

New Lines Institute’s Fresh Voices blog aims to showcase new talent in the sphere of foreign policy, geopolitics, and analysis. The pieces here reflect the mission, vision, and values of New Lines, and serve as a space for fresh voices to showcase their ideas, recommendations, and analyses. These pieces allow readers to consider viewpoints from outside established policy circles and understand new ideas and perspectives.

The Saudi-Iranian Rapprochement and the War in Yemen

This spring’s rapprochement between Saudi Arabia and Iran has breathed new life into direct negotiations between Riyadh and the al-Houthi rebels in Yemen. But it would be shortsighted to assume that these efforts will bring a true end to the war in Yemen. First, there is no guarantee that Iran can stop the al-Houthi fighters from battling Yemeni government forces and launching cross-border attacks. Second, there is plenty of reason to believe that the rapprochement between the Saudis and the Iranians will be short-lived. Finally, the peace efforts are less likely to succeed until they include other key Yemeni stakeholders.

The China-brokered normalization agreement between Saudi Arabia and Iran was announced on March 10, but it was the result of years of negotiations in Baghdad. Under the accord, Riyadh and Tehran agreed to reopen their embassies within two months. They also agreed to reimplement a pair of agreements – one in 2001 establishing security cooperation and another in 1998 covering cooperation in sectors ranging from trade and investment to science and culture – that had been suspended since the countries broke off relations in 2016.

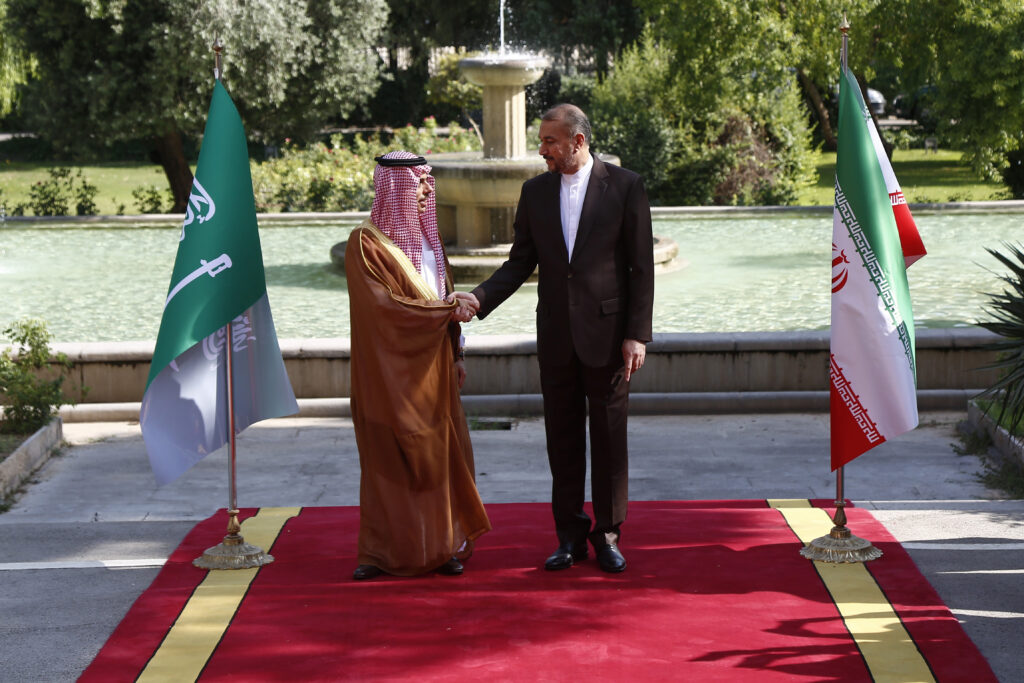

Less than a month after the announcement, Iranian Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian held talks in Beijing with his Saudi counterpart, Prince Faisal bin Farhan al-Saud. The meeting was the highest-level engagement between the regional adversaries since they cut ties seven years ago. Relations had been severed after Saudi Arabia executed a popular local Shiite cleric and Iranian protesters retaliated by setting fire to the Saudi Embassy in Tehran.

Yemen Needs Relief

Reports in the Wall Street Journal that Tehran agreed to stop arming the al-Houthis and encouraging their attacks on Saudi Arabia remain unconfirmed, but there is already diplomatic progress between the al-Houthis and Saudis themselves. On April 9, the two parties met in public in al-Houthi-held Sana’a to discuss a more permanent cease-fire. No official cease-fire has been announced, but the two sides released hundreds of prisoners days later in a major confidence-building measure that has seemingly reassured the international community.

Hope for a permanent cease-fire couldn’t come at a better time for Yemen. While a U.N.-brokered truce agreement expired in October, neither side has launched a major offensive in the months since. The al-Houthis have refrained from attacks on Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, and the Saudi-led coalition has abstained from conducting airstrikes in Yemen. However, the relative peace in Yemen is fragile, and isolated fighting between the al-Houthis and the Yemeni government in Taiz, Marib, and Shabwah governorates could soon escalate. Moreover, the al-Houthis threatened attacks on Saudi coalition members if Riyadh backs out of a de-escalation agreement with the group.

There are major problems with assuming that a deal between two of the war’s chief backers will mean an end to hostilities in Yemen. For one, there is no guarantee that Tehran could stop the al-Houthis from conducting attacks. Al-Houthi officials took to Lebanese television shortly after Riyadh and Tehran sealed their agreement to make it clear that the group was not subordinate to Tehran, and as such the deal would have no impact on the war in Yemen. An al-Houthi spokesman went so far as to say, “Even if Saudi Arabia signed a joint defense agreement and [formed a] military alliance with Iran, that wouldn’t protect it from us, so long as it continues its aggression against us.”

There is some truth to these statements. Despite what many people think, the al-Houthis are not a proxy that acts solely on behalf of the Iranian regime. The group has its own history, agenda, and ideology firmly rooted in the al-Houthis’ interpretation of their Zaydi religious background. This means its priorities differ substantially from Tehran’s. While plentiful evidence suggests the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps and its proxy Hezbollah provide the group with arms, training, and financial support, the al-Houthis act autonomously. In just one example of the rebels acting out of line with Iranian interests, the al-Houthis launched several cross-border attacks on the United Arab Emirates in January 2022 despite recent rapprochement efforts between Tehran and Abu Dhabi.

Even if Tehran can influence the al-Houthis’ plans, Iran might not have an interest in releasing its grip on Yemen in exchange for a reconciliation with Saudi Arabia that could be short-lived. After all, this is far from the first time since the 1979 Iranian Revolution that the two sides have tried to mend relations. They signed cooperation agreements in 1998 and 2001 – as mentioned above, those agreements were reinstated as part of the rapprochement in March – but the countries’ security and economic interests diverge too greatly, and neither deal brought much success.

All Parties Should Be Included

A deal between the Saudis and al-Houthis might be in the making. But an agreement limited to those two parties would not necessarily portend an end to the war in Yemen. The negotiations as of now do not include the internationally recognized Yemeni government or other major Yemeni stakeholders, and many observers fear the result could be an agreement that only benefits the al-Houthis and the Saudis. For instance, the Saudis could agree to withdraw from Yemen in exchange for an end to al-Houthi cross-border attacks. This would not end the conflict within Yemen.

Moreover, the negotiations don’t include the Presidential Leadership Council, or PLC, the Yemeni government’s eight-member executive body that includes representatives from across political, ethnic, and tribal lines. The PLC’s exclusion means its parties will not feel obligated to abide by the deal. It will also erode the body’s legitimacy within Yemeni society, further weakening the already fractured anti-al-Houthi coalition.

Instead of supporting ongoing al-Houthi-Saudi talks, the United States and the international community should push for a more inclusive dialogue in Yemen. These talks should bring in the PLC, which includes a representative from the Southern Transitional Council, an organization advocating independence for southern Yemen that is aligned with a number of powerful militias. They should also involve Riyadh’s main coalition partner, the United Arab Emirates. The U.N. is seemingly aware of this and is pushing both parties to engage in a more inclusive peace process. During a meeting with Iranian officials shortly after the Iran-Saudi deal was announced, U.N. Special Envoy to Yemen Hans Grundberg discussed expanding peace negotiations into an inclusive, Yemeni-led peace process under UN auspices. However, there’s no sign of this effort being undertaken for now.

Getting the al-Houthis to the table with Yemeni government representatives will be difficult; the rebels have publicly stated they will not sign an agreement with the PLC. But the U.N., U.S., and the international community should focus on incentivizing the al-Houthis to participate. Economic inducements such as the payment of government salaries in areas under al-Houthi control and the reopening of ports and airports will likely be the most effective. The al-Houthis have prioritized these demands in recent negotiations, likely fearing that poor economic conditions and worsening humanitarian crises in areas under their control could erode their support from local populations. But once the al-Houthis are at the negotiating table, the international community will have to develop new incentives, like pledging funds for Yemen’s reconstruction, that entice the rebels and other parties in Yemen to observe a permanent truce.

Emily Milliken is the Senior Vice President and Lead Analyst at Askari Associates, LLC. She is a frequent commentator on Middle East and Africa with her work published by Al Jazeera, Newsweek, The Hill, the National Interest, and the New Arab, among others. She holds an M.A. in Middle East Studies from Johns Hopkins SAIS.